-

Humanoids in Wafer FABs – update

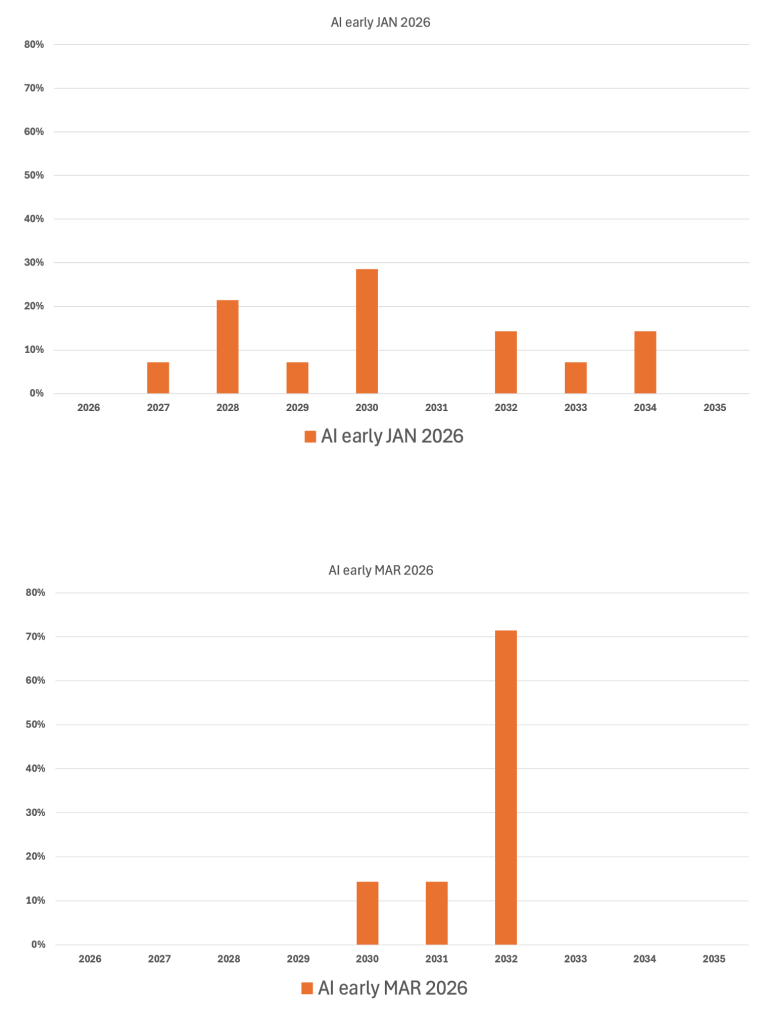

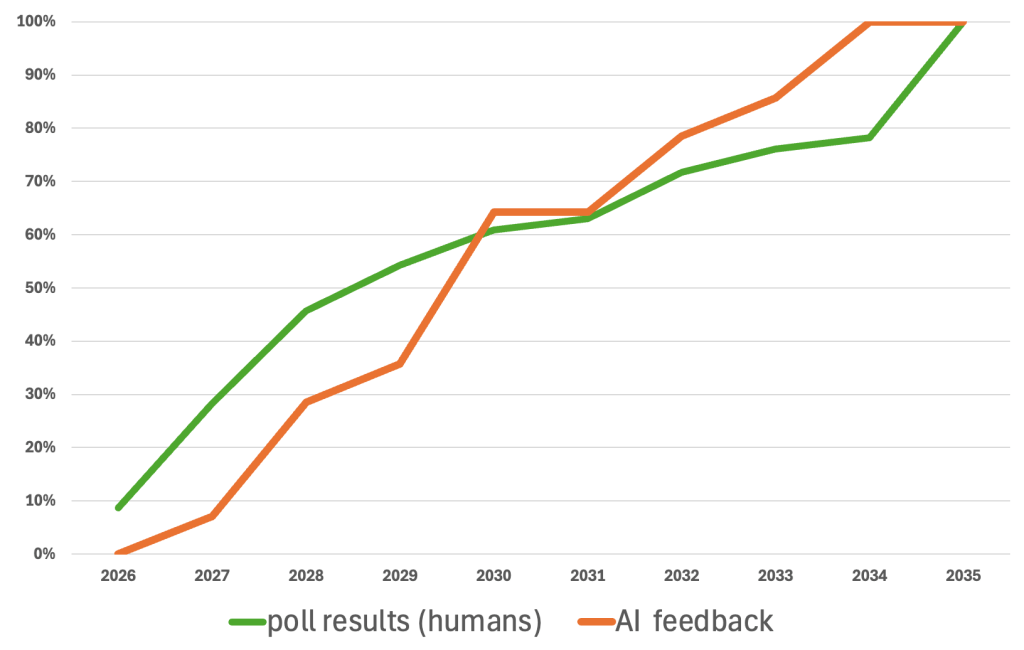

I was curious what the world of AI thinks 2 months after the initial poll and gave the same chatbots the exact same prompt like I did in early January.

To my big surprise the picture changed indeed – significantly !

Below is the comparison of the 2 response to the prompt:

It is very interesting to see, that almost all models now come to the same conclusions and I wonder is this because of they all use now more and more the same underlying data or is the underlying data itself no more “precise” and points towards a 2032 date.

Another interesting fact was that most models mentioned in their response, that

-

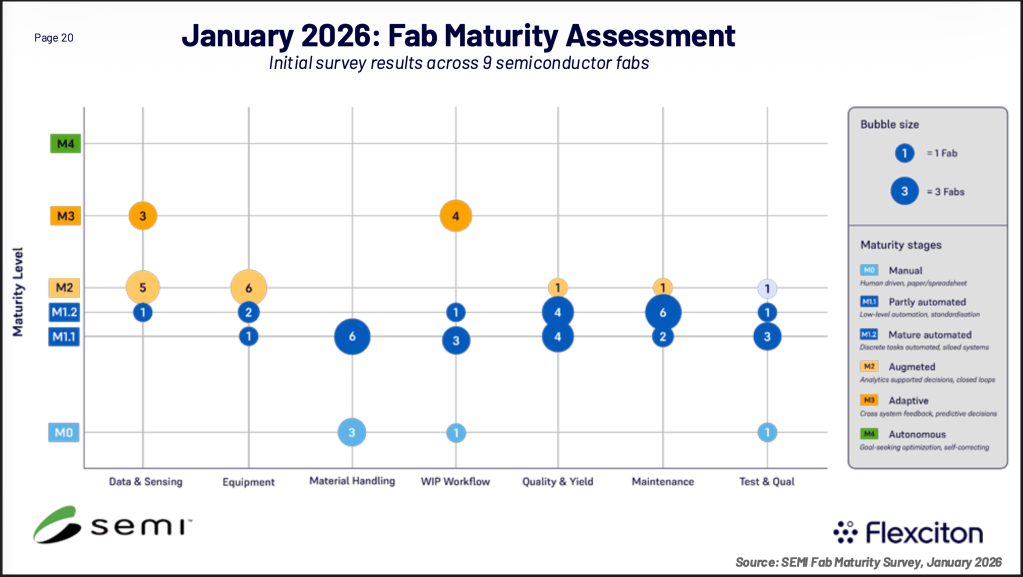

Legacy FAB Automation Maturity – Update

I like to share the latest update of the SEMI effort regarding legacy FAB Automation Maturity.

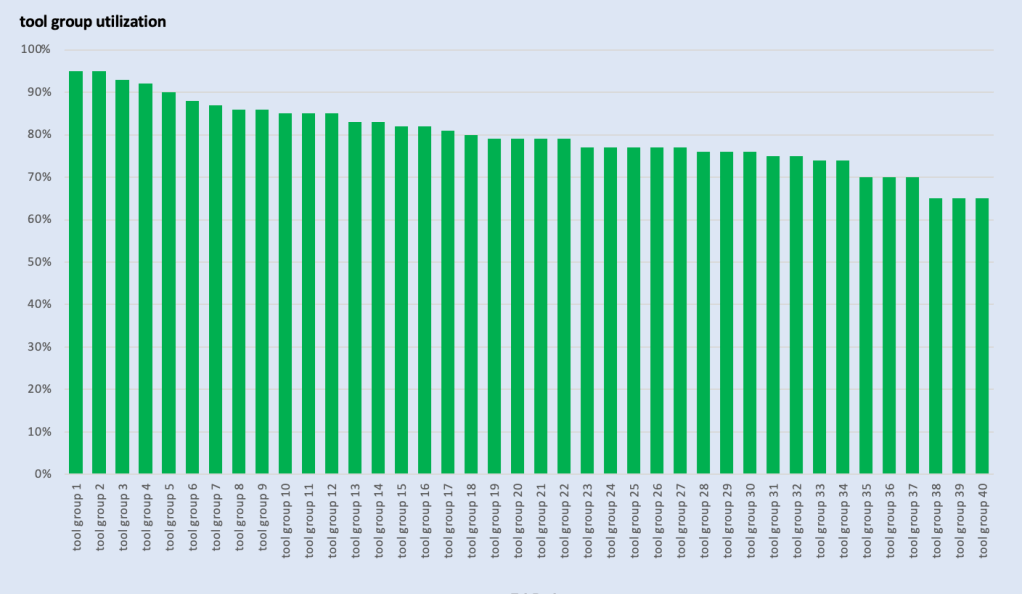

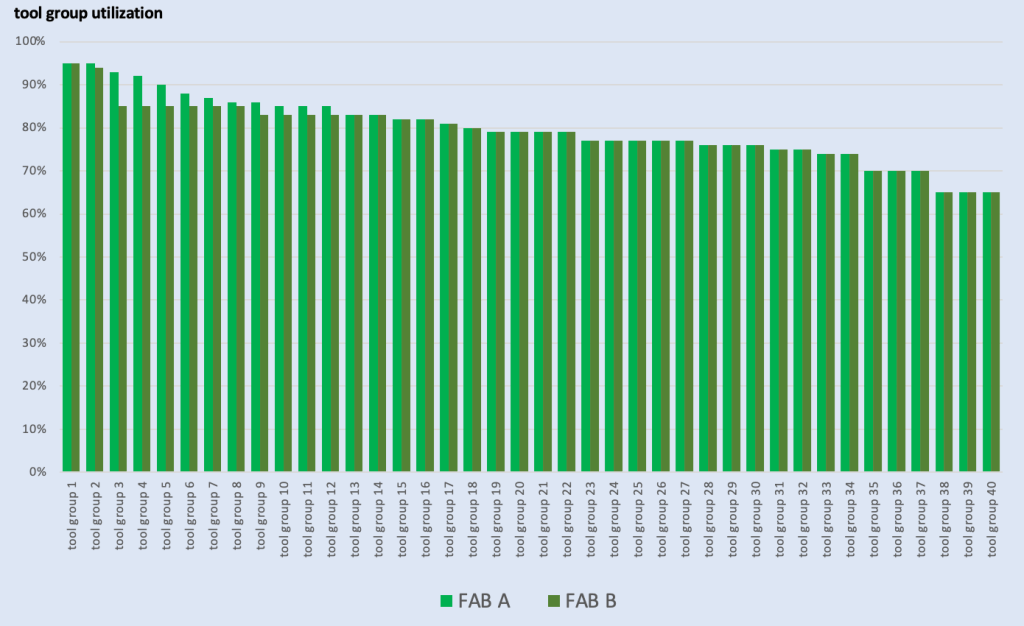

Dennis Xenos from Flexciton presented last week at the Innovation Forum in Dresden, Germany the latest results – there is now data from 9 FABs available:

The complete presentation can be found below:

The team is still looking for more FABs and industry experts to participate – if you have interest in joining the effort please reach out to

Anshu Bahadur, email: abahadur@semi.org

-

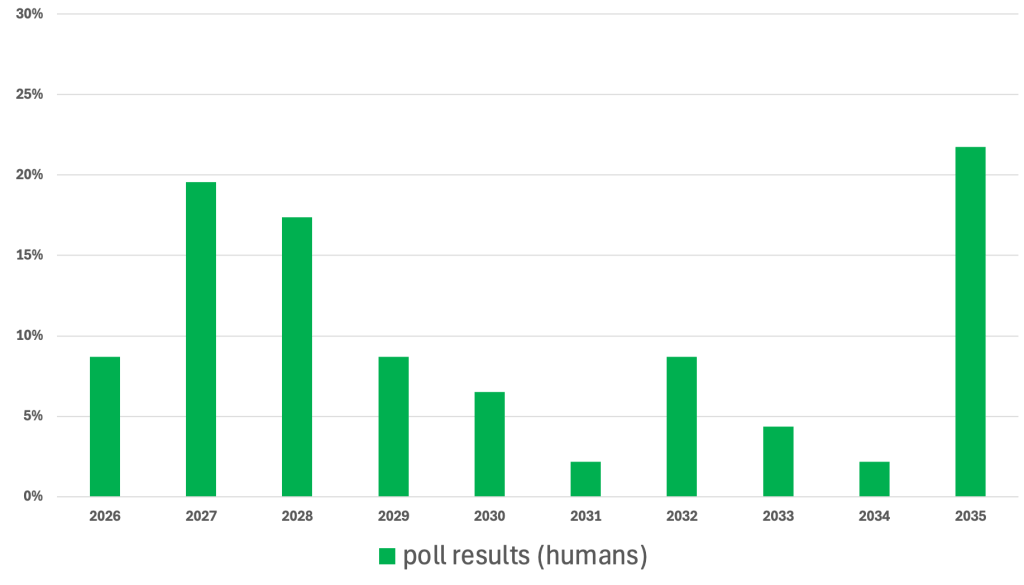

Humanoids in Wafer FABs – poll results

First of all I like to say thank you for the active participation. As we just saw at CES – humanoids are “really everywhere” – but it also seems there is a long way to go to see these comrades in real productive deployments.

Here is the poll result:

Based on this data about 50% of the voters expect deployment within the next 3 years, but there is also a large fraction which points to a much later date.

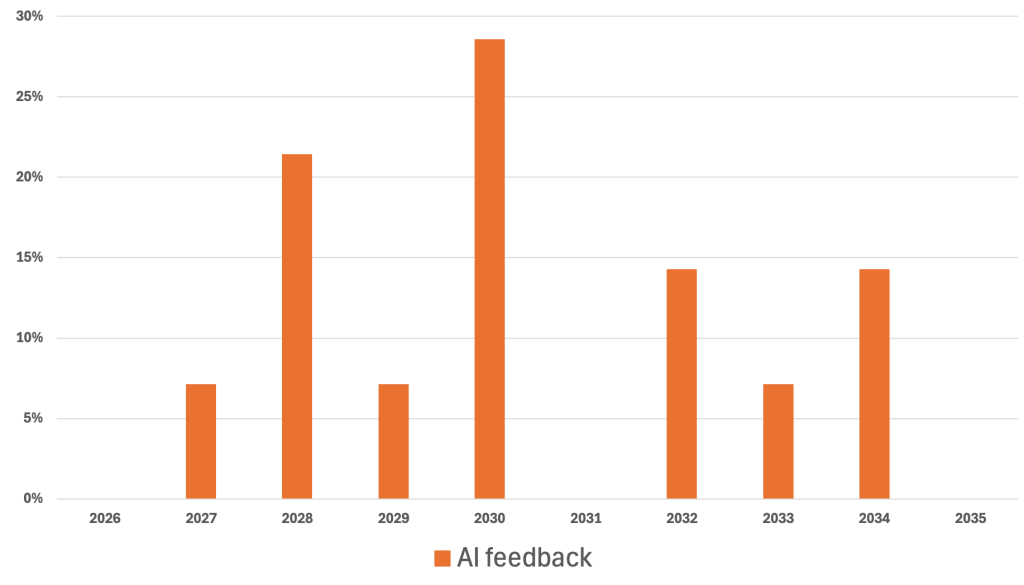

I was curious what ChatGPT & Co. think about this topic and asked a bunch of different AI tools and also did this within 3 weeks twice – and yes, the same AI app changed sometimes the expected deployment date between the 2 inquiries by up to 2 years.

A cumulative chart comparing the two results shows this:

The AI feedback was generated by using this prompt:

“I like you to act as a technical researcher and planner. In which year will we see the first humanoid robots working in regular production in semiconductor frontend wafer fabs. Please list the top 3 facts you have used for your estimated year and back it up with data. Please tell me the year, when you have 80% confidence that the humanoid robots are deployed – not in test mode, but in normal production, executing wafer carrier transport as well as process tool loading and unloading fully autonomously. I’m only interested in your estimated year for fabs in the US or Europe, not in Asia”

This prompt does not only deliver a simple date, but a few interesting statements and remarks about the what and how of the deployments – give it a try yourself !

When it will really happen – only the future will tell us – but one thing is sure: If your company wants to be a front runner for this effort the start of the work on how to integrate humanoids into the Wafer FAB software ecosystems needs to happen very soon.

Lastly, I ran into a nice video talking about humanoids in homes – which I think is an even more complicated deployment – worth watching.

So with all this – when do I think we will see a humanoid in a wafer FAB ? Being a technical optimist I say it will be sometime in 2028 – 2029.

Thank you for following and reading my blog.

2 responses to “Humanoids in Wafer FABs – poll results”

-

A thought:

Why does the world need humanoid robots? My bold hypothesis: it doesn’t need them at all. At least not for technical reasons. Perhaps for psychological reasons: for example, if robots work with people in need of care, it would be helpful if they could speak and move like humans. But in a factory? There are better automation solutions than imitating humans. Do you know how complicated it is to replicate just a human hand? Let’s abandon this delusion. In a factory, we need solutions. They can look like humans, but they don’t have to.Translated with DeepL.com (free version)

LikeLike

-

-

Humanoid Robots in Wafer FABs ?

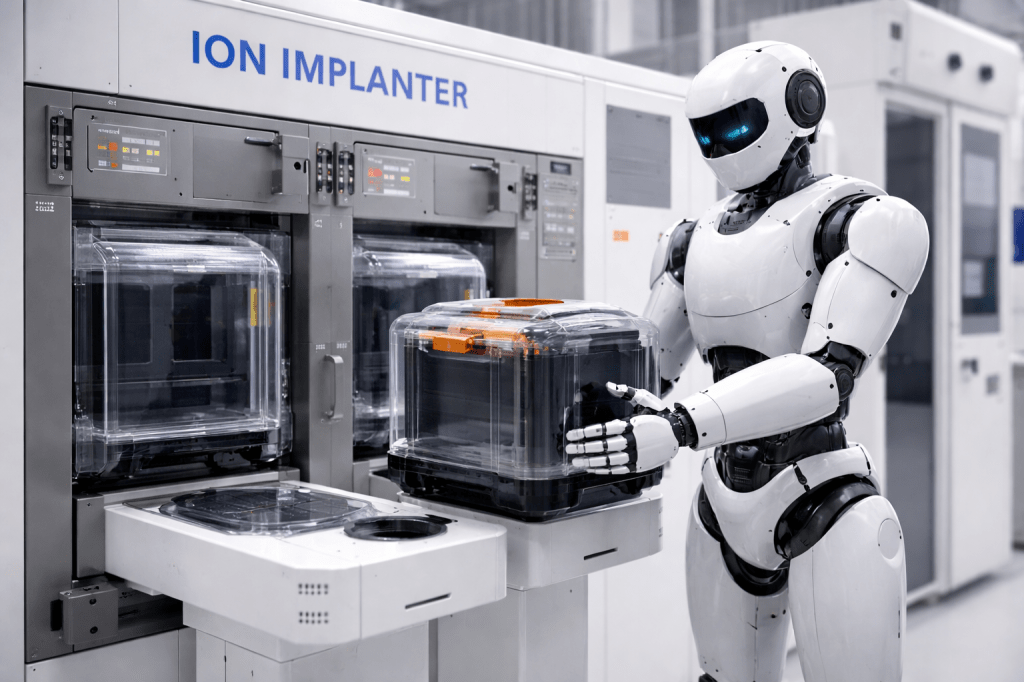

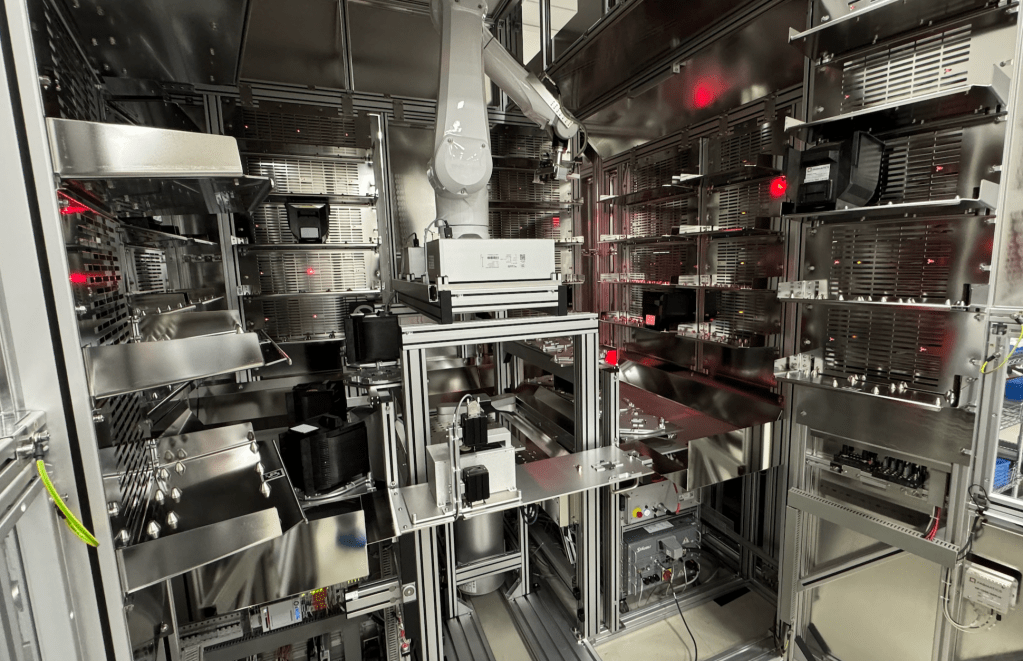

As the activity and hype (?) around humanoids heats up there is one question lately in my mind: When will we see the first humanoid robots in wafer FABs in regular production ?

Since the overall trend towards more generic robotic hardware is gaining traction the human form factor will fit of course very well in all older wafer FABs which have no OHT capable automation systems – largely because of too low ceilings and recessed equipment load ports. In todays application often AGV/AMR solutions are deployed, but as humanoids will eventually become commercially available.

Obviously there is still some significant work to be done especially for topics like:

- physical safety ( what happens if a robot falls)

- working in hybrid environments with real humans

- gripper capability / flexibility

- run times per charge

- how long will it take to train and commission and humanoid

To have generic humanoid robots which will be able to work the next day in a different FAB area – just by a software change – would be the ultimate benefit.

I also think there will be some work needed to integrate humanoid robots into the typical FAB software environment:

- will they be controlled by a traditional MCS or fleet manager ?

- will humanoid robots “speak” SECS/GEM and E84 ?

Besides all these challenges I believe humanoids will find there way into the wafer FAB automation world: be it

– to transport wafer carriers

– load / unload process tools

– transport spare parts to support maintenance crews

– execute the complete maintenance work from start to finish.I’m curious what you – the reader of this blog – think. By when will we see the first humanoid robots doing regular production work in a wafer FAB in the US or Europe ? Please participate in the poll below.

I will share the results next year in my next post.

Happy Hollidays !

-

Maintenance in the era of Industry 4.0

I recently run into a very nice article written by Jeff Winter – discussing the evolution of maintenance approaches. I thought it is absolutely worth sharing here.

Thank you Jeff for giving me permission to do so. More interesting articles by Jeff can be found here:

https://www.jeffwinterinsights.com/Please see the article here:

-

Legacy FAB Automation Maturity Framework

In the last 3 months there was a working group under the umbrella of SEMI working on a Maturity Framework – and the 1st results were presented at the SemiCon West last week in Phoenix, AZ.

I had the opportunity to contribute to this work. The attempt is to give existing 200mm Wafer FABs an idea where they rank in terms of automation and autonomy – and eventually a guide where to start with the efforts to catch up.

With the increasing pressure from chips made in Asia – especially legacy nodes technology based – there is only one way to stay competitive: get more output out of the existing factory – ideally with less cost.

Automation and eventually Autonomy using advanced algorithms ( I did not say AI !) will definitely be the way.

Below you can find the presented slides:

As always, the more FABs participate, the better will be the outcome and quality of the frame work. If you are interested to participate – see contact information on the last slide of the attached file.

-

Results of FAB Automation 2025 survey

I like to thank everybody who participated in the survey in the recent weeks. The survey had 5 different focus areas:

– 100/150mm Frontend FABs

– 200mm Frontend FABs

– 300mm Frontend Fabs

– Assembly/Test/Backend

– non semiconductor hight tech FABsUnfortunately, only the 200mm Frontend section got enough participation to assume that the results are statistically relevant. Not sure how to explain the “silence” of the other areas – maybe automation is not a hot topic there at all.

Nevertheless, I think the results for the 200mm Frontend FABs are very interesting and to some part surprising.

I would love to hear your thoughts about the results in the comment section of this post !

The survey results can be found here:

Leave a comment

-

State of Semiconductor FAB automation in 2025

In a recent discussion with my colleague Wesley Capar – talking about FAB automation and what the overall situation in the current difficult business environment might be – we came up with the idea to ask YOU – the industry experts on your opinion.

Since the situation is likely very different between state of the art 300mm FABs and older legacy facilities, I structured the survey in 5 individual parts. The questions itself are 100% identical in each survey – the only difference is for which facility type your answers are coming from:

- 200mm Frontend FABs

- 15mm/100mm Frontend FABs

- 300mm Frontend FABs

- Assembly/Test/Backend FABs

- other high tech / clean rooms FABs

The results of the surveys will be posted once they are in.

Thank you for reading and participating – it will take less than 10 minutes of your time.

Below are the 5 surveys:

Please use this survey if you are answering for a 200mm Frontend FAB:

Please use this survey if you are answering for a 150mm/100mm Frontend FAB:

Please use this survey if you are answering for a Assembly/Test/Backend FAB:

Please use this survey if you are answering for a 300mm Frontend FAB:

Please use this survey if you are answering for other high tech / clean room factories:

-

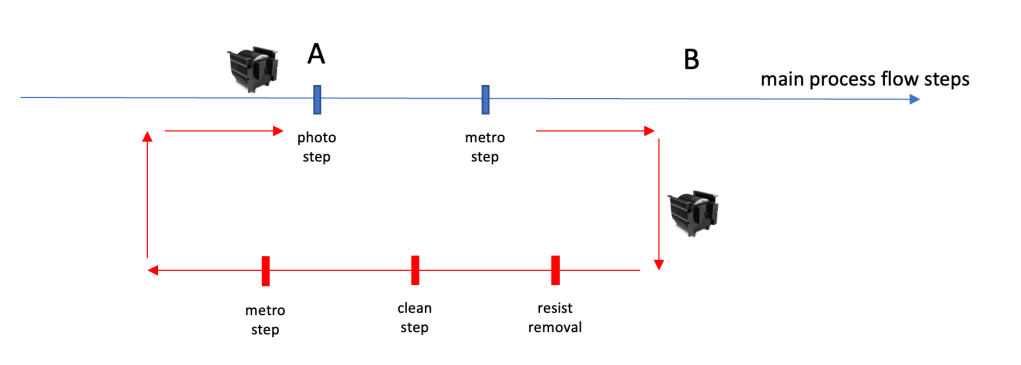

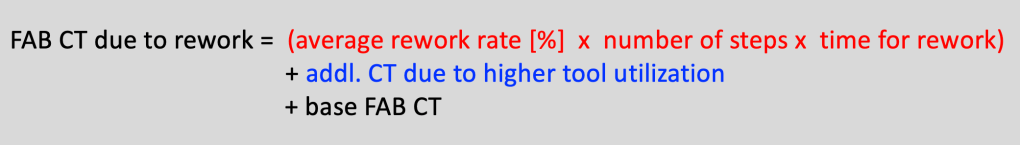

Importance of carrier location tracking – part 2

This post will be all about the advantages and capabilities of RFID based carrier tracking.

But before I dive into this – here are the results from the poll from part 1:

Based on this more than half of the legacy FABs have no complete location tracking of all carries in place. In my opinion this is not surprising. A main reason for this situation is that all these FABs are running production for many years and have found work arounds to limit the impact of the missing exact location tracking. A great part of these work around processes play humans – who are able to search and locate carriers. Of course this comes at the cost of spending the time for searching – which reduces FAB productivity.

As competition increases and the ever ongoing fight for reducing the cost per wafer in the FABs leads FAB managers to start thinking about automating material transport and handling – exact location tracking becomes a must. As discussed in part 1 of this blog there are various methods to achieve this, but the quasi industry standard is using RFID.

How does RFID work ?

Every carrier to be tracked needs to have some form of a RFID pill or RFID tag attached to it. This tag holds information about the tracked carrier, for example the carrier ID. In order to locate a carrier every place where a carrier can be placed needs to have an RFID Antenna which can detect and read the RFID tag information.

There is a fundamental important (and kind of hidden) meaning in this statement:

every place where a carrier can be placed needs to have a RFID AntennaFor true 100% location tracking no carrier is allowed to be placed somewhere without a RFID antenna. (classic examples for this could be shift leader tables, WIP overflow shelves, …)

When introducing RFID based carrier tracking a lot of existing FAB policies will need to change – but more on that later.

Here is a picture about the general infrastructure needed:

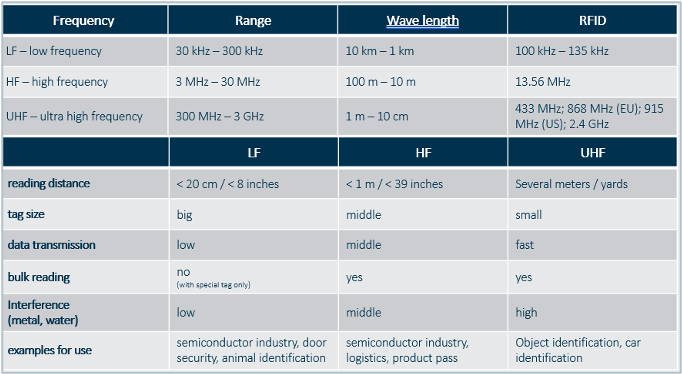

There are different frequencies for RFID system available on the market:

All of them have their individual strengths and weaknesses, but in the semiconductor industry the low frequency or LF is the quasi standard. Greater 95% of all FABs which use RFID based carrier location tracking use LF – biggest reasons for using LF are:

- very short reading distance (avoids cross reading of multiple RFID tags , for example in shelves or nearby load ports

- very narrow bandwidth ( helps in the general high radio frequency noise inside the FABs)

- plenty of different antennas available to accommodate antennas to be placed in difficult physical locations (like tight load ports)

Like already discussed in part 1 of this post there are many benefits of having good location tracking in place:

- no more time lost for searching carriers (lots)

- effective FAB scheduling is possible

- basic enabler for automatic material transport and handling

- basic enabler for automated process start on equipments

What makes RFID based material tracking the better choice over bar code scanning based solutions are things like

- highly reliable (not dependent on good lighting)

- many tool load ports come standard with RFID reading capabilities or can be easily upgraded

- no human interaction needed (hand scanning) – massive time savings possible

A few thoughts on how to approach an project to change a FAB to RFIDIntroducing or changing carrier tracking methods are a complex task since a lot of existing policies might change. Change in itself always brings some risk with it and if it is involving possible productivity and/or wafer loss – sensitivity is extra high. Since every FAB has some form of carrier identification and location management in place (see part 1 of the post) the desire for change and improvement typically comes from cost pressure – either reduction in operator cost and/or growing plans to automate carrier transport, handling and decision making

A fundamental decision to be made at the very beginning of such a project is:

What is the end goal – in 5 or 10 years ?What is the expected automation level of the FAB in 10 years from now ? Will the FAB always have operators or is the plan to have eventually 100% automation of “everything” ?

The statement:

every place, where a carrier can be placed needs to have a RFID Antenna

often raises fears on the overall cost of such a project.But at a second look there is seldom a big bang event possible, where “overnight” everything has to be changed and in place. One big advantage of RFID based ID and location tracking is: It can be easily implemented in phases. In other words, there can be a long lasting hybrid approach used. Some areas start using RFID other keep doing what they do today. There might be even cases in older legacy FABs where not all locations and equipment load ports can be outfitted with the needed RFID hardware – but why not harvesting the benefits on 85% of all the others ?

The only true initial cost is that all to be tracked carriers need to have an RFID pill or tag attached to it.

What will it cost ?

Let’s assume the FAB has 6000 carriers (cassettes for example).

Depending on the RFID tag or RFID pill vendor, the cost should be around $10 or so. So we are talking $60,000 for the whole FAB.

In addition, there might be cost on how to attach the pill or tag to the carrier. This depends on what is already available at the existing carrier. In the best case there is zero additional cost (pill or tag holder already existing) or there will be very manageable additional cost to weld holders on the carrier.

The bigger cost driver is the actual roll out of the RFID antenna / reader / Ethernet connection boxes. The good thing is, it can be rolled out very step by step. For example: to start with RFID antennas for a certain tool group, just the RFID reader hardware needs to be procured and installed on these tools. This is anyway a recommended great 1st step to iron out any possible integration efforts with the local FABs MES system. Once this is working – maybe even including “load and forget” scenarios to automate process starts on the selected process equipment – further roll out can be planned better.

Using this approach the total project cost can be distributed over years if desired and the most beneficial tool sets (high operator effort for example) could go first …

Final Thoughts

For existing legacy FABs with aged process and metrology equipment one key aspect of such a project is to make sure that all desired equipment can be upgraded with reliably working RFID reading hardware.

I strongly recommend to partner with an RFID expert like (spoiler) FABMATICS (LINK) to test in your FAB at your specific equipment which antenna and reader combination works best for each tool type, shelf or buffer location- at the lowest possible cost – basically mounting RFID tags and antennas in various positions with actual carriers.

If you are early in your project and still free in decision making, here is my general recommendation:

- partner with an experienced RFID Semiconductor FAB retrofit company, not only for hardware and software, but also for the general concepts ( for example should you use re-writable tags or not as well as what capability you MES can provide)

- go with LF RFID solutions – if possible with pills

- plan for complete full automation in the future, to make sure your RFID infrastructure selection can support this longterm (number of different antenna types possibly needed) as well as AMHS and robotic systems which support RFID based ID tracking (way more reliable than bar code)

- plan to start with a pilot tool set

- run this pilot in production for some time and learn

- roll out tool group by tool group

-

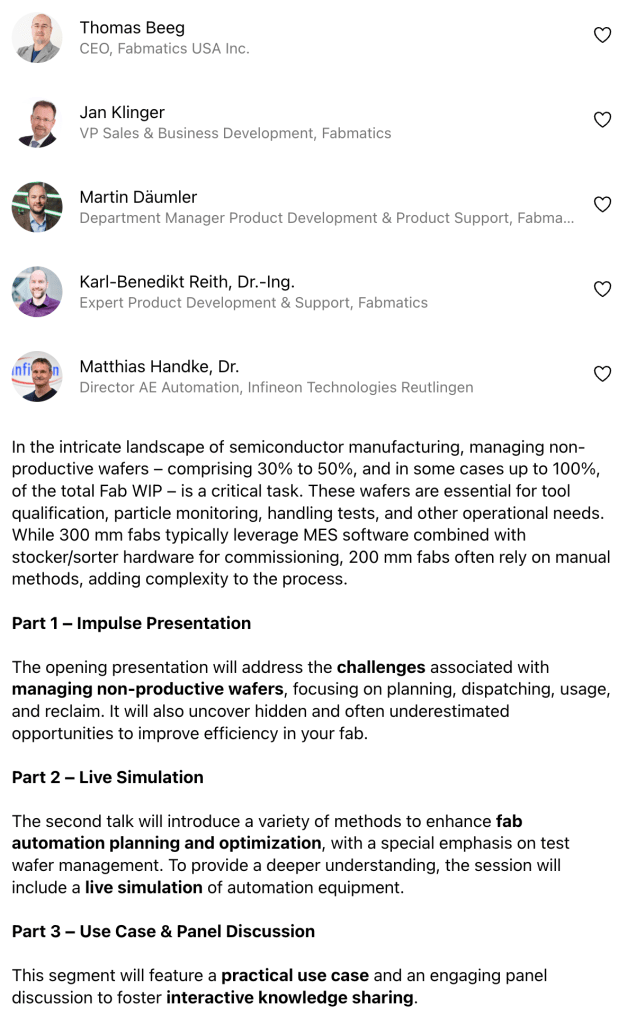

Innovation Forum for Automation 2025

To make it short: We had a blast !

The 22nd edition of the conference took place in Dresden, Germany last week and I had the honor to play an active part. Together with a few of my colleagues from Fabmatics Germany we hosted the break out session

Test Wafers – the hidden GEMS in your FAB

It was a packed room and all three presentations stimulated a very active Q&A session which clearly showed that the topic is still hot in the industry. This was the session layout:

here you can find all 3 slide decks:

On day 2 of the event I had the opportunity to participate in an expert panel to discuss hot topics of the semiconductor industry – specifically for the none-leading edge eco system.

On both days plenty of interesting talks were given – but one was especially eyebrow raising in my mind:

Dr. Matthias Meyer from the Fraunhofer-Institute talked about soon to be established regulations for cyber security in the European market space. If you are active there – please have a look here:

Finally, a few impressions from the event – a big thank you to Automation Network Dresden/Photographer: Sven Claus, who was providing the pictures for this post.

-

Good Bye 2024 – Hello 2025 !

Another super busy year went by like a breeze – and I like to wish all my readers a great Holiday Season and a good start into 2025.

Speaking of 2025 – there will be 2 great conferences early next year which I plan to attend and I like to raise your interest.

Innovation Forum for Automation in Dresden, Germany

The agenda was just published and there will be again great topics to listen and learn from:

AGENDAI will be an active participant this time – talking with some of my peers from Fabmatics about

Advanced Semiconductor Manufacturing Conference – ASMC in Albany, NY

As a member of the Technical Committee of the ASMC I just participated in the conference prep meeting and we put together a great selection of presentations and posters. The final agenda has not been published yet – be sure to check the ASMC website in the next weeks.

Maybe you will be at one of these 2 events, too – looking forward to meet in person.

Until than – Happy Holidays !

Thomas

-

AI enabled precision maintenance

I’m very happy to have another guest post to publish ! During the last SEMI Fab Owners Alliance (FOA) meeting in Portland, ME

David Meyer, co-founder and CEO at Lynceus AI and

Ariel Meyuhas, COO and Founding Partner at MAX Grouppresented a very interesting approach using AI to improve equipment maintenance. I think this is a really nice approach to tackle a long existing problem in the industry. I approached David and Ariel to share there work here – Enjoy reading !

AI-enabled Precision Maintenance

This blogpost follows a presentation made at SEMI FOA session in October 2024. The slides are attached below.

AI-Enabled Precision Maintenance: a new way of managing capital capital equipment

As you all know, servicing tools becomes increasingly complex and PM checklists keep growing. If we keep thinking about maintenance in the same way, we risk degrading COO and profitability. On the brighter side, there is now abundant data to describe equipment behaviour and the technologies that can leverage this data are getting more and more mature.

This is an opportunity to provide a step-change in equipment productivity.

Current Maintenance Paradigm: long, rigid and blind

Here is the problem: we are used to fixed PM schedules. At every PM, we run through the same list of actions – irrespective of what’s actually happening to the tool / process.

As a consequence, our PMs are long, rigid and blind.

This negatively impacts PM downtime, qual complexity, spare parts consumption and even unplanned downtime. The time we spend on unnecessary interventions is time we could have spent troubleshooting more accurately or implementing longer term fixes.

Now, what if we could run PMs differently? what if we could do only what is necessary, when it is necessary?

This is what AI-enabled Precision Maintenance aims for.

A new maintenance concept

We came up with the concept of a dynamic and fractional PM checklist based on real-time status of the tool and of the process. Concretely, for each part of the tool and at any given time, we can recommend whether or not an intervention is required.

We formulate this recommendation based the tool’s maintenance history and on its most recent behaviour.

With AI-enabled precision maintenance, you’d be able to access real-time recommendations, for each part of the scope: how many wafers can I still produce before change? is the tool behaving normally or not?

This tool has the power to optimize PM scheduling and inform the engineer on which parts of the PM scope to execute or not.

This translates into:

- Shorter G2G

- Simpler PM, and therefore simpler quals

- Reduced spare parts consumption

- Improved team productivity

As a fab manager, it gives you the possibility to optimize for COO, productivity and capacity simultaneously. The concept was tested on a bottleneck toolset with manual extraction of data, which is very labour intensive.

Combining expertise

Rolling-out AI-enabled precision Maintenance successfully requires a combination of different skills & expertise working together.

First, deep Maintenance & Equipment expertise: MAX Ops defined the Precision Maintenance concept and demonstrated its impact through manual implementation. We know it works, but it is still more empirical than systematic.

Then, we need to make it scalable. AI techniques help extract and leverage information from equipment data automatically, which then feed dynamic PM checklists.

The last piece of this puzzle is of course the users in the fab. Adopting such a novel approach to capital equipment management requires a true partnership with the fab, in order to define the best way to validate, deploy and use this tool.

Impact on Operations

While AI-enabled precision maintenance is a new concept, Precision Maintenance is not.

At MAX Engineering, we have been supporting fabs in optimizing their maintenance cycles by defining more frequent, more fractional scopes – with some great results.

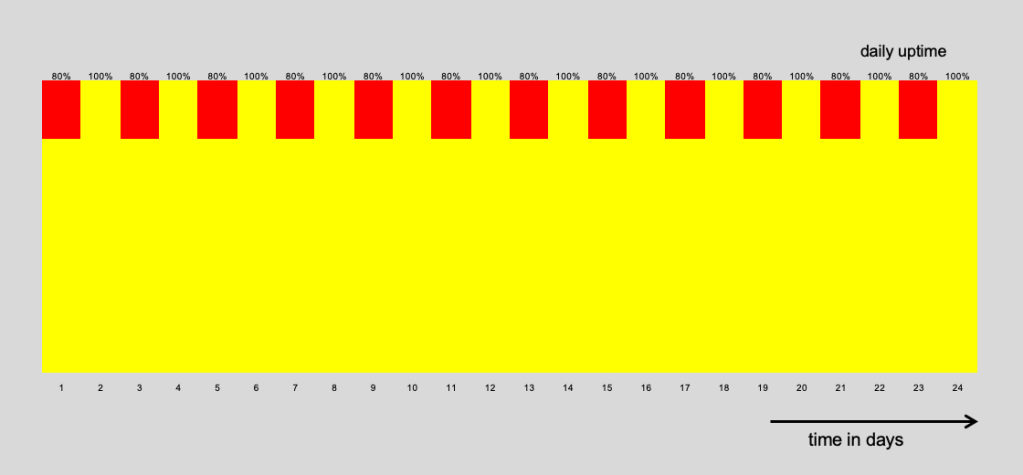

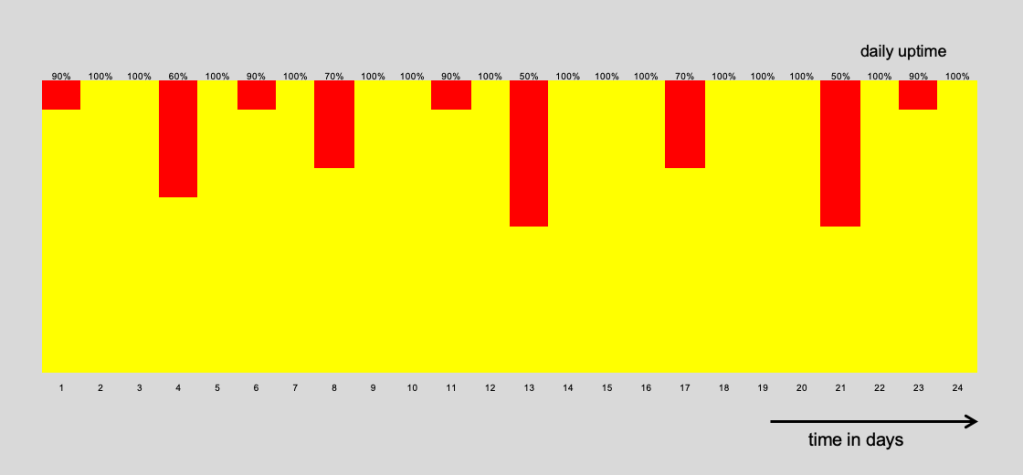

In this example, we were working on a set of Litho tools in a 300mm fab.

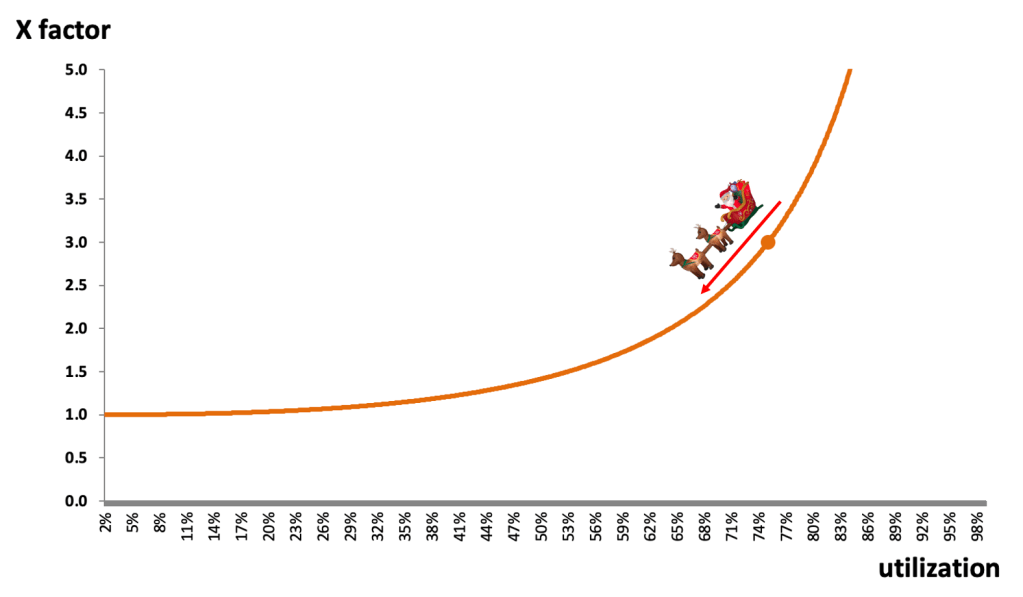

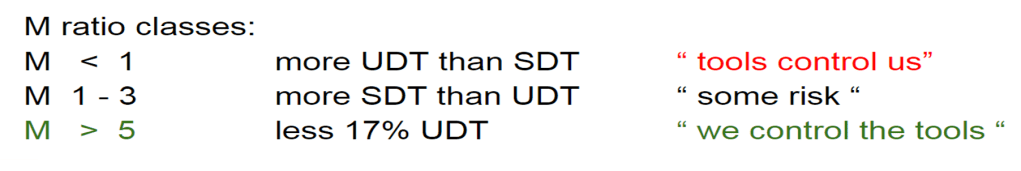

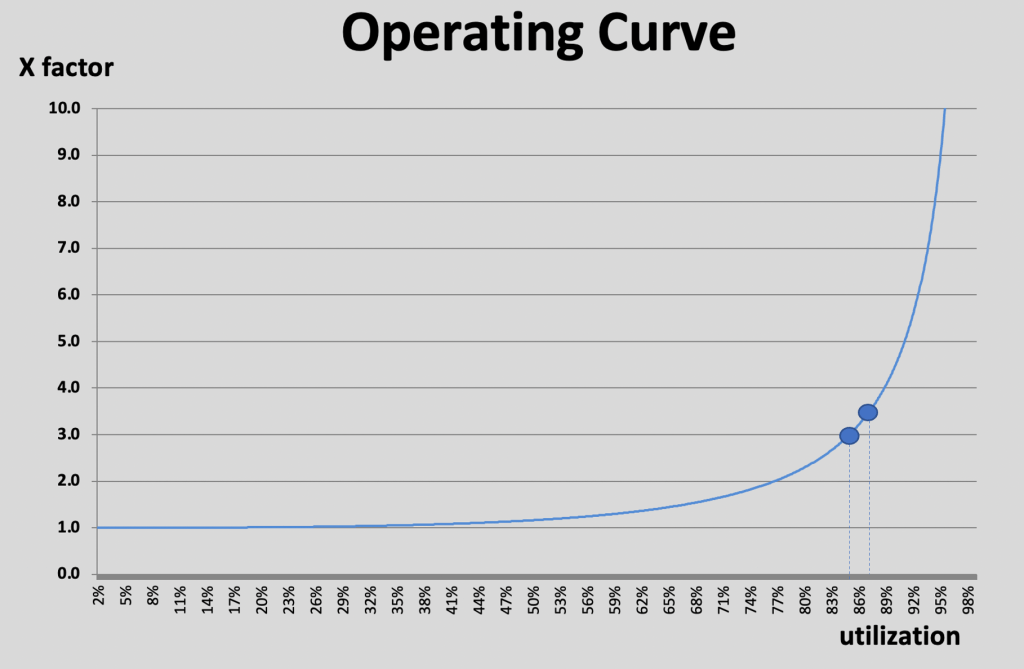

Precision maintenance helped this fab reduce G2G time by 25% on average and improve M-Ratio from 3 to 5:1. On an annualized basis, this means 4% net uptime gains.

Now this is what you can obtain by breaking down PMs into smaller fixed scopes, through a highly manual and empirical process.

So what is the expected impact of boosting Precision Maintenance with AI?

First, we would be able to define dynamic PM scopes, updated in real-time based on the tool’s most recent behaviour. We expect this can double the productivity gains evidenced with Precision Maintenance, parts & people combined.

Second, we could replicate this approach seamlessly to other bottleneck areas in the fab, 6 times faster than if we had to redo it manually. At scale, this means turning local uptime gains into realized throughput expansion.

Looking forward: AI-Module Engineer Assistant

To conclude, I’d like to give you an idea of what the future of module engineering can look like.

We saw that AI-Enabled Precision Maintenance will be a step change in maintenance productivity, but this is only step 1.

We are already working on an AI module engineer assistant, able to perform most of the routine tasks around process & equipment management. We imagine a tool that can:

- Flag drifts in equipment behaviour

- Define maintenance checklists based on the tool’s most recent behaviour

- Publish and share reports on recent PMs

- Build correlation studies around events of interest

- Support technicians during interventions

This is step 2, and we’re working on it today.

Here is the complete presentation from the SEMI FOA meeting:

If you are interested to learn more, please contact David or Ariel directly:

David Meyer : david.meyer@lynceus.ai

Ariel Meyuhas : ariel_meyuhas@maxieg.com -

Importance of carrier location tracking – part 1

When looking on the topic of improving Wafer FAB performance – the topic of lot and/or carrier tracking is often not in focus. For fully automated 300mm FABs this is really not an issue, because it is fully covered using RFID tags/pills on the FOUP and have any possible place where a FOUP can “sit” outfitted with RFID antennas. This ensures that at all times the exact location of a FOUP (and the associated lots) is known.

For legacy FABs running 200mm or 150mm the topic of carrier and lot location is far from being standardized and solved.

Why is it important ?

In Lehmans terms: if the location of a carrier (and the lot or lots) is not exactly known, it might create wait time and lost tool utilization since “someone” needs to “search” for it. These little search times can easily add up and become a problem. If a FAB wants to go from a more manual material transport and handling to a more automated solution the topic becomes very critical.

But even in manual FABs the real time knowledge of the current location of a carrier can have big impact.

A typical use case is to move from pure lot dispatching towards lot scheduling to improve the overall FAB cycle time and tool utilization. Without exact lot location a schedule is “worthless” since the schedule can not be executed. Because the lot is not available when needed. I have in person witnessed legacy factories which had scheduler deployed, but more than 10% of the WIP’s location was not known and therefore the schedule could not be executed. Typically the quality of the scheduler solution gets questioned , but the real problem is the unclear lot location data situation.

Let’s explore the situation – specifically for not fully automated factories

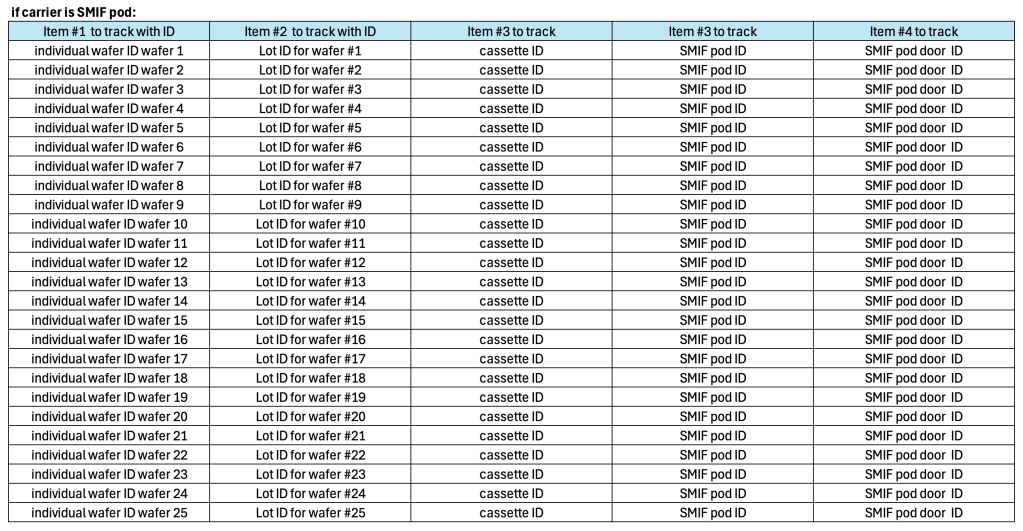

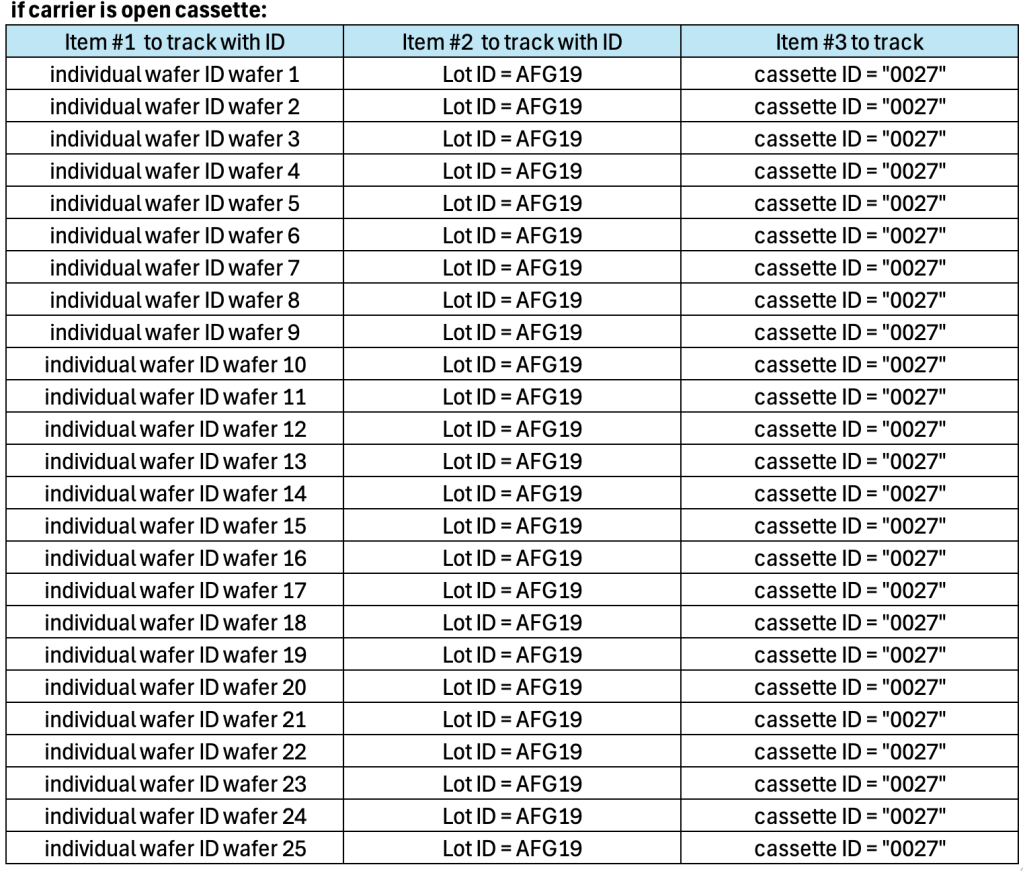

The first interesting thing to discuss is the lot and carrier identification itself. Depending on the used carrier in the FAB the complexity is different. The tables below show the theoretical depths of the problem:

For practical reasons not all of the items might be tracked in the real FAB application.

How are the individual parts ID’ed ?

There are different methods used for different parts.

Wafer identification

Individual wafers are typically tracked by using a physically laser scribed ID number directly on the wafer. This means the ID is fix for the lifetime of the wafer – it cannot really be deleted and given a new ID.

A lot ID is not a physical thing, which can be location tracked since a lot ID is a virtual entity residing in the MES. Multiple individual wafers (and their ID number in the MES) are logically grouped and called a “lot”. Common approach is that all wafers of one lot have the same target product and will be put in the same carrier. The mapping of wafer ID to lot ID traditionally happens at lot start in the FAB and will be stored and tracked in the MES.

Cassette identification

In the early days cassettes were ID’ed by putting labels with a form of code – typically bar code – on it. Additionally to the bar code there is often a human readable number on the label. To locate a cassette for example in a WIP rack, a human would scan with his/her eyes the rack until the cassette is found.

Example:

In the example above only 2 ID would be visible to humans or machines on the physical cassette: the cassette ID and if looked very close, the individual wafer IDs. The lot ID is usually not visible on the cassette, unless an additional lot ID label is recreated and attached to the cassette.

Therefore humans in the FAB often look for the visible carrier ID when searching for “a lot” but not really for the lot ID.

Using barcodes on the cassettes brought the advantage to use bar code scanners for data entry into the MES and therefore eliminating possible human errors while manually entering awkward lot and carrier ID into a computer terminal. Downside of the label with code method is that there are physical code scanner devices needed – many of them. In the real FAB 24/7 often these scanners create problems, especially if they are wireless and have rechargeable batteries. Network stability in fully packed legacy factories is often a challenge and battery life as well is “where is the scanner ?” create additional risk for lot processing delays.

A second – way more capable method of ID-ing cassettes – is the usage of RFID tags or pills. These pills can hold multiple sets of information and can easily be re-programmed with new content. The possibilities and advantages of RFID based carrier identification and location tracking will be topic of part 2 of this post.

Lot box identification

If a FAB uses cassettes in a box another element for tracking comes into play,. Should the box be tracked with an ID for the box itself on top of the cassette ID ? In my opinion the answer is yes. There are many advantages of doing so:

- boxes and cassettes might be restricted for usage only in certain zones (FEOL, BEOL, Copper , …)

- in a manual FAB, the box is what humans will see in most cases (since the cassette is inside)

- when cassettes are loaded onto an equipment load port the empty box needs to be stored “somewhere”. In many cases the same box should be used again once the cassette is done with processing

- there are steps in the process flow, when wafers need to be moved from the transport cassette into a special processing cassette – without ID it will be a risk to mix ups

- in case of equipment break down during process wafers from multiple lots, cassettes and boxes might need manual recovery – huge potential of mix ups, if proper IDs are missing

One typical question which needs to be answered when setting up cassette and box ID is: How is the relationship between the 2 defined.

For example:

At lot start a brand new cassette and brand new box will get for the 1st time an ID label, lets assume

Cassette ID = WC0028 and the Box ID = WB0028

Wafer ID will be assigned to a lot ID and after that the wafers get physically moved into the cassette and the cassette into the box. What will be the FAB policy regarding to the cassette to Box relation ?

Option 1: WC0028 always needs to be in WB0028

Option 2: there is no hard requirement for following Option 1 always, WC0028 can be for example transported in WB0017, as long as such a change is tracked within the MESBoth cases have their pros and cons, but in my experience option 2 is the most used one.

There are also cases where the box itself is transparent or has a transparent window and the cassette ID can be read by humans through the box. In these rare cases sometimes the box is not tracked with an own ID – with all the downsides of that.

SMIF Pod identification

SMIF pods introduce a 3rd part which could be tracked since the “lot box” now is a Pod which has 2 individual physical parts – the dome and the door. In general all statements from the section lot box identification can be made for SMIF Pod as well. The most interesting question for SMIF Pods is:

Is there value in tracking dome and door individually ? The answer depends a lot on 2 things:

1. Has the MES the capability to easily track additional objects ?

2. Does the process provide contamination risk, if the wrong door gets put on a dome ?

Now that the basic principles of the identification of carriers are discussed, let’s look into the location tracking aspect. In general location tracking for my purposes here mean:

“to know, where a specific carrier (carrier ID) is right now in the FAB”

There are 2 sub topics here: “Where” and “right now”

“Right now” is a simple correlation to date and time. If this data is available and stored in a computer system, then also the historical positions of a carrier can be looked up. The more interesting part is the “where”.

Although there are tracking systems available, which track “indoor GPS style” using X, Y and Z coordinates, it is more common to have defined places as the “location”, examples:

- Stocker 17 in bay 5

- incoming WIP ETCH bay rack 1

- load port 2 at equipment ID ETC003

- shift supervisor desk in main aisle

- on cart 3 of intra-bay transport system

- WIP rack 22, position 6

- push cart 4 (on the way to Litho area)

All these “locations” have some context related information and humans will remember, where WIP rack 22 is physically located. The interesting aspect here is, that humans are capable to use relatively “vague” locations like “it is in WIP rack 17” to hopefully quickly find the specific carrier – by browsing the carrier rows and look for the carrier ID.

How is the “carrier ID to location” relationship established and available for users (humans or machines) ?

There needs to be some form of track in / track out mechanism into a specific loaction.

for example:

- when a carrier is placed into a rack , the carrier ID as well as the rack id get bar code scanned

- when a carrier is placed on an equipment load port, the carrier ID and the load port ID get bar code scanned

- when a carrier is placed on a WIP Rack, the location is manually entered in a MES terminal

- or in its simplest form, without any tracking: “all incoming WIP to this bay gets placed in to the “incoming WIP rack”

The quality of the location data and its resolution can have a big impact:

” it is in rack 17″ might be good enough for a human, but if there are plans to automate material transport “it is in rack 17” will be a hard showstopper or at least very time consuming for a robot to scan all possible individual rack locations.

In general it can be said, the better the location data resolution is, the faster a carrier can be “found”.

In fully automated 300mm FABs any possible location a carrier can be in is individually specified and has an individual location ID. These are used by the MES and MCS system. For legacy factories with 150mmm oder 200mm wafers this location resolution is much more coarse.

I’m curious what nowadays the typical location data quality is. If you have knowledge about this topic in 150mm and 200mm FABs ( please no 300mm data ) please answer the poll below:

I will share the results in part 2 of this post.

Thank you for reading.

-

Test Wafer, part 3

In the last few weeks I had the opportunity to visit a few of our (FABMATICS) customer FAB’s here in the US – sure enough the topic of test wafers and the options and benefits to automate test wafer handling came up in all of them.

They all categorized themselves into the area of higher test wafer to product wafer ratios ( see the 1st post of the test wafer series) and mentioned they feel they have way to many test wafers in the FAB. Most of them also talked about challenges in getting tool time on process equipments to build new or recycle used test wafers.

From my own experience this is very common in less automated FAB’s where a lot of day to day decisions are still made by humans – who are often measured by daily or hourly production wafer moves.

To get a good control over the huge number of test wafers and the high number of different test wafer products one key starting point is to have transparency about test wafer WIP levels, use rates and who owns which test wafer.

I think to have a chance to be successful the general FAB mindset needs to be that test wafers have the same importance as production or engineering wafers.

This means that test wafers are completely modeled and tracked in the FAB’s MES system and test wafer lots are “running” on test wafer routes or flows – exactly like production wafers. This will not only enable real time monitoring of the test wafer status, but also opens up the capability to schedule and dispatch test wafers automatically using the FAB’s scheduling systems.

Test wafer Modeling

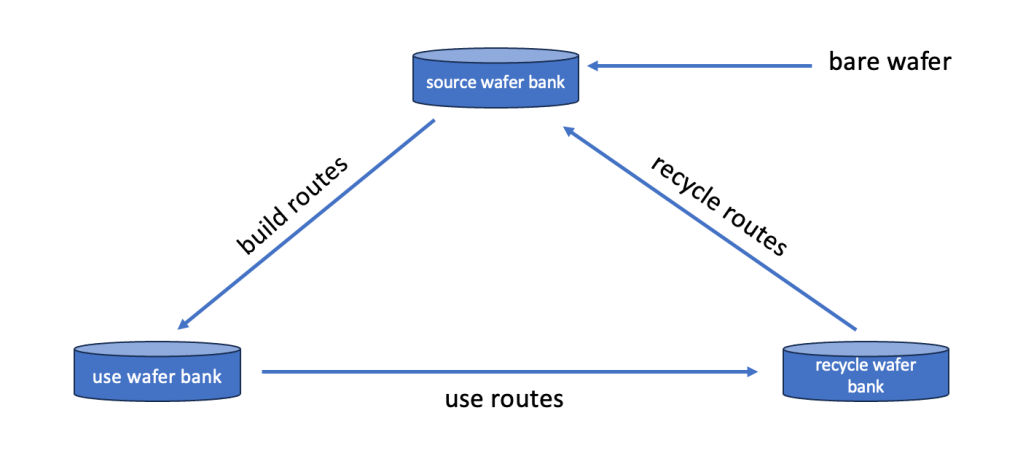

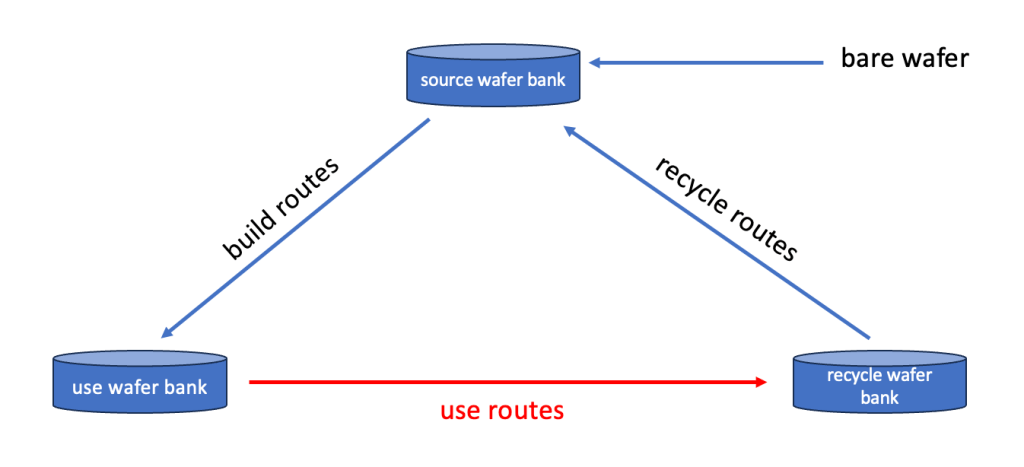

There are many ways of modeling test wafers, but one successful way of doing this is to follow the general life cycle of test wafers. A typical one would look like this:

- newly bought bare wafer

- built desired test wafer type

- use test wafer

- recycle test wafer

- scrap test wafer (end of life)

A graphical representation of such a cycle would be this:

Lets walk through the cycle on an hypothetical example for the following case:

After a maintenance event on a dry etch tool there needs to run a particle test wafer as well as an etch rate test wafer to confirm the the chamber is in spec for release to production. In order to so they need to be ready for use when the maintenance work is done.

Lets assume:

1. the particle test wafer needs to be of a certain cleanliness before it is used on the etch chamber

2. the etch rate wafer needs to have a known thickness of a certain filmBuild routes

to prepare or “build” these wafers the following 2 routes might be used:

Particle wafer route:10 – start wafer from source wafer bank

20 – clean wafer at wet clean tool

30 – measure particles at metrology tool

40 – grade wafer – if below needed particle count -> o.k. to use

50 – store wafer in use wafer bank

Etch rate test wafer route:10 – start wafer from source wafer bank

20 – clean wafer at wet clean tool

30 – measure particles at metrology tool and if good:

40 – deposit needed film on wafer at deposition tool

50 – measure film thickness

60 – grade film thickness – if good:

70 – store wafer in use wafer bankSince it takes time to “build” these wafers it is clear that this has be done in advance of the actual use else their is high risk that the test wafers are not ready in time.

Another aspect of the build process is that of course not a single wafer will be build, but instead full lots (like 25 wafers per carrier).

This also means in the use bank there are likely multiple ready to use wafers sitting in the same carrier.Use routes

To be able to actually “use” the 2 wafers for our post maintenance check, again a couple of things need to happen, which is typically managed by using “use routes” examples for or 2 wafers could be:

Particle Test wafer

10 – start wafer from use wafer bank

20 – split out 1 wafer into an empty new carrier

30 – run (cycle) wafer through the etch chamber

40 – measure particles added by the etch tool

50 – if particle adders are in spec – set flag in MES to “good to use in production”

60 – grade wafer – if still good for next use – send back to use bank, else

70 – store in recycle wafer bankEtch rate test wafer

10 – start wafer from use wafer bank

20 – split out 1 wafer into an empty new carrier

30 – run etch rate recipe at the etch chamber

40 – measure new film thickness at thickness measurement tool

50 – if etch rate is in spec – set flag in MES to “good to use in production”

60 – grade wafer – if still good for next use – send back to use bank, else

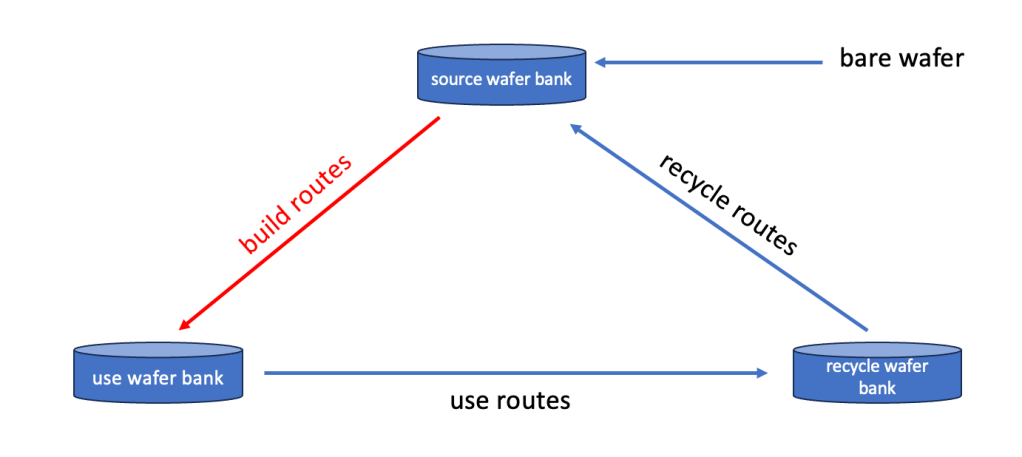

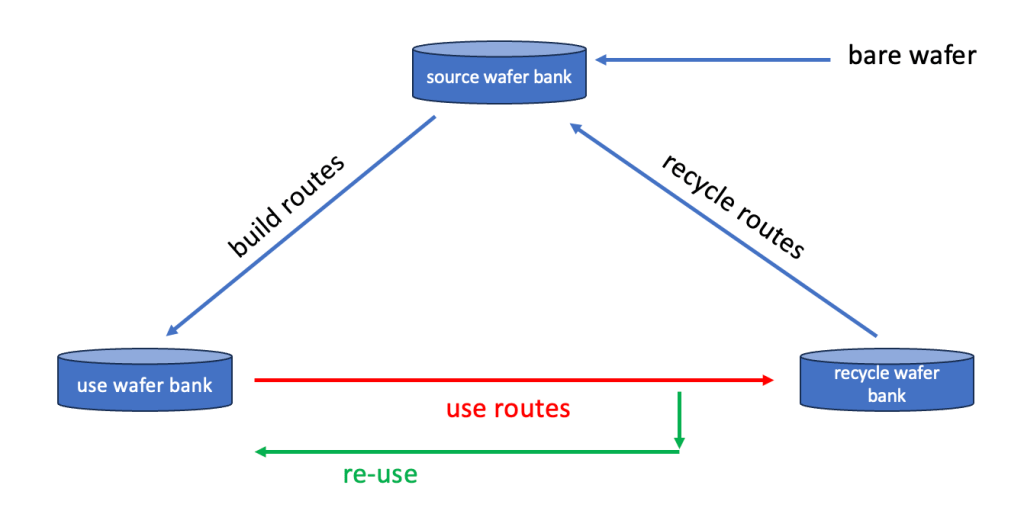

70 – store in recycle wafer bankbased on the option of directly re-using an already build and used wafer the model becomes this:

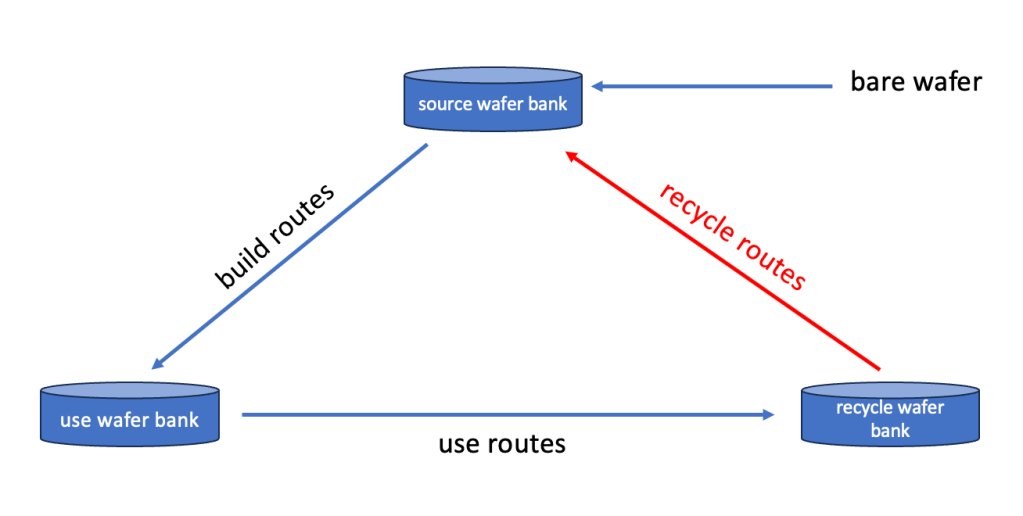

Recycle routes

Lastly, but also very important – what to do with all the used wafers ?

For cost saving reasons most FAB’s have implemented in-house recycling flows to “clean” the used wafers and put them back as “like new bare” wafers in the source wafer bank

For our 2 wafers (very likely in one lot/carrier together with other similarly used wafers sitting in the recycle bank) these routes could look like this:

used particle test wafer:

10 – start lot from recycle wafer bank

20 – clean wafer at wet clean tool

30 – measure particles at metrology tool

40 – grade wafer – if below needed particle count -> o.k. to use as “like new”

50 – store wafer in source wafer bankused etch rate test wafer:

10 – start lot from recycle wafer bank

20 – completely etch all remaining film from wafers at etch tool

30 – measure film thickness ( should be zero now)

40 – measure particles and if good

50 – store wafer in source wafer bank

These examples of routes are of course extremely simplified. I conveniently ignored to describe all the needed lot ID and product ID changes which are involved in this life cycle, but it should be good enough to illustrate the principle.

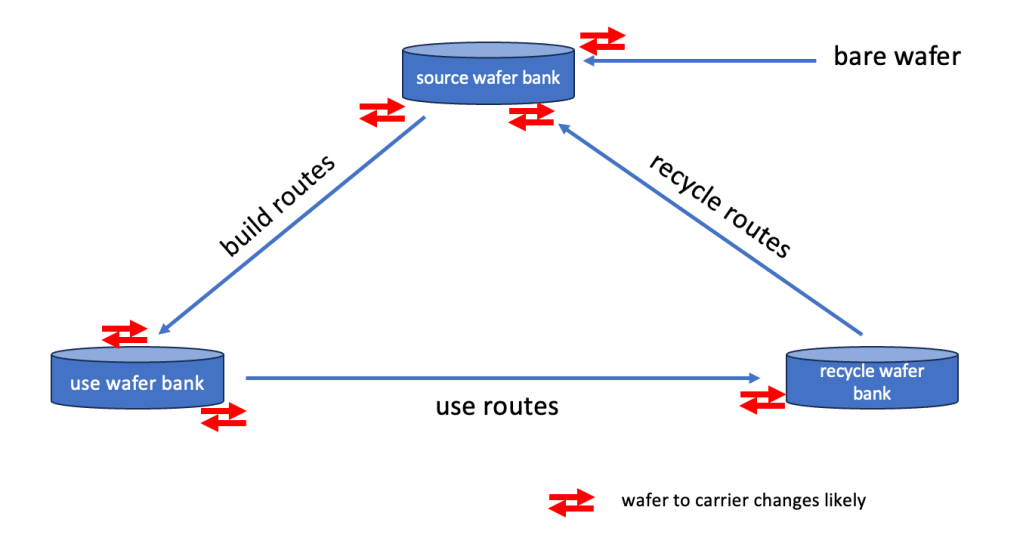

A key part of the test wafer process is the frequent change of wafers into different carriers. Typically these happen at least at the read marked “points” in the flow:

Depending on how automated a FAB is this can be a massive effort and drives a lot of operator time. Therefore the test wafer process it is a prime target for automation efforts.

Final thoughts

There are many more aspects of how to model and run test wafers in a FAB, which all have their pros and cons as well as depend on general policies the FAB applies: A few of the more interesting ones are:

- Do the FAB policies and CIM system capabilities allow multiple different lots to be stored and transported in the same carrier ?

- How is test wafer ownership organized ? For example: do different areas manage their own test wafers or is it allowed to share for example particle test wafers with other areas ?

Depending on how this is organized it might reduce the overall amount of test wafers – or not. - How are minimum and maximum stock levels at the 3 wafer banks defined ?

- How and where are test wafer lots stored and tracked from a physical location point of view ?

“somewhere in one of the 3 shelves over there” vs. in a stocker – makes a big difference - Do FAB policies require fresh pre-measurement data before each use or can old post measure data be used to save time. And if yes, how old can the data be ?

- How often can wafers be recycled before they are not usable anymore ?

- What is the scheduling/dispatching logic for test wafers on build and recycle routes at process tools which also run production lots ?

- Is there regular test wafer WIP level and test wafer aging reporting set up ?

- Who owns the test wafer “business” in general ? Operations ? Engineering ?

- Are there dedicated engineers assigned to manage test wafers in the FAB ?

- What happens if a test wafer in use case comes back with data out of spec ?

Is it a simply re-do of the test wafer run – and if yes – is it automatically a second run ? - How many of the traditionally on test wafers done tasks can be done directly on product wafers (at what risk) to save test wafers altogether ?

- Is there data available on how often process equipment has extended down time due to no test wafers ready ?

- Which of the test wafer uses cases are “gating” – meaning the process tool tested has to wait until post measurement data is available ?

- What is the frequency of scheduled test wafer runs? daily, weekly, every 10 days …

- How advanced is the deployment of run to run controllers to avoid seasoning, warm up or send ahead wafers ?

I’m sure I missing a lot more aspects. One thing is clear, test wafers have a huge impact in a FAB – and based on everything written above this is not a small “Friday afternoon” task.

To manage this “zoo” successfully:

1. test wafers need to have the same importance as any other wafer in the FAB

2. a well defined set up in MES is needed

2. ownership needs to be defined

3. engineers need to be allocated / dedicated

4. automating the kitting, de-kitting as well as the transport of test wafer carriers will significantly improve efficiency (spoiler alert: Fabmatics’ TESTWAFERCENTER can help with exactly that)Happy Test Wafering 😉

-

Test Wafer, part 2

First of all, thanks to everybody who participated in the test wafer usage poll in the last post. I received some decent feedback and below are the results:

For 150 and 200mm FABs (based on 15 data entries)

The data show that test wafers play a massive role in the day to day FAB business. Most FABs have significant amount of test wafers as well as allocated carriers to test wafers.

For the 300mm FABs:

The general theme is the same, but there are 2 important remarks to make:- there were only 5 feedback votes – it seems in 300mm the overall competition might be tighter and the willingness to share data is limited – so the data above might be not a good reprensentation of the 300mm situation overall

- there were 2 data sets indicating less than 10% of carriers are used for test wafers – this is interesting since the overall test wafer percentage in the FABs is still high.

My guess is that in 300mm FABs with the high material transport automation capabilities there might be single wafer stockers in use to store test wafers outside of FOUPs.

Overall, the data set from the polls show a picture which I was expecting. Test Wafers are plenty in the FABs and they consume a lot of carriers as well as storage space. Here is a high level thought to get a feeling for real numbers:

Let’s assume a small/mid size wafer FAB has the following WIP related indictors:

- 10,000 wafer starts per week

- average 30 mask layers

- 1.8 days per layer cycle time on product lots

- average lot size 24 wafers for product lots

That will translate into an overall FAB production WIP of about 80,000 wafers, which will sit in about 3,400 carriers. Based on the poll data that would also mean that this FAB has an additional 50,000 … 90,000 test wafers sitting in 2,000 … 4,000 test wafer carriers.

I think this is mind boggling – at least compared to how much is typically talked and written about test wafers and test wafer management.

So how come that there are such massive amounts of test wafers in the FABs ? For sure it has to do with the impact of test wafers – especially when they are missing. ( see the part 1 of the test wafer post)

In my next post – which will be the 3rd and final part for the test wafer topic – I will discuss some of the common strategies and methods:

How to have control over these massive amounts of test wafers and test wafer carriers and how to make sure that equipment uptime is not (too often) impacted by missing test wafers.

-

Test Wafer , part 1

Inspired by the recent LinkedIn post from Fabmatics about the TestWaferCenter (LINK)

I thought it is time to look a bit closer at the general topic of “test wafers”. So what are test wafers ?

To keep it simple I will use the term “test wafer” for any non-product wafer in a FAB. Test wafers are the unsung hero in every FAB – almost like electricity and water in your home – you really only notice them when they are not available. Typical variants of non-product or “test wafers” are:

- wafers to qualify / re-qualify a process equipment after a maintenance event like thickness, etch rate or particle measurement wafers

- conditioning wafers, used to ensure process conditions in an equipment are ready to run product wafers, for example after longer idle times or recipe changes

- filler wafers typically used in batch furnace equipment to fill up empty wafer slots in the process boats

- monitor wafers – which are processed in parallel to product wafers in an process equipment to measure certain process results

- mechanical handling wafers used to teach / re-teach robots and general wafer handling inside of process equipment

- calibration “golden” wafers used to re-calibrate metrology equipment

In contrast to these wafers there are of course the product wafers, which are the wafers most people care about in a FAB:

- regular product wafers ( will contain at the end of the process real chips)

- R&D wafers – future product wafers ( will contain at the end of the process real chips)

- short loop wafers – to experiment and learn at certain segments of a real product process flow

The interesting thing about test wafers: these have massive impact on the overall FAB productivity:

a) in a positive way – by being always available when needed

b) in a negative way – by being not available when needed – for example after maintenance of a process equipment – missing qualification wafers will extend the equipment down time and therefore reduce the FABs capacityIn one of my past roles at a wafer FAB – every once in a while in the morning meeting we had reports about process equipment being extended down, since the needed test wafers were not available (in time) – obviously not a good situation to be in.

The fix to this situation seems easy – have the test wafers ready … ?!

But what does this mean exactly and how to make sure that this indeed works as desired ?

Unfortunately, the topic is very complex and it starts with the typically very large amount of different types of needed test wafers. The challenge is not only to have “a test wafer” available when needed, but the “right” one. To ensure the availability of all needed types of test wafers, FABs will have stock levels of these wafers and if summed up it can add up to impressive overall numbers of test wafers in a FAB.

One useful indicator on how complex the test wafer topic in a FAB is, is the ratio between product wafers and test wafers.

For example:

if a FAB has a total product WIP of – let’s say – 100,000 wafers and in parallel has also about 20,000 test wafers “sitting” in the FAB the ratio would be 100,000 : 20,000 or 1 : 0.2if a FAB has a total product WIP of 100,000 wafers and in parallel has also about 100,000 test wafers “sitting” in the FAB the ration would be 100,000 : 100,000 or 1 : 1

In my 29 years in semiconductor I have seen vastly different product to test wafer ratios and I’m super curious what the situation looks like nowadays. The need for test wafers also is a function of the criticality of the process nodes running in a FAB. For that reason I divided the poll below into 2 groups:

- 300mm FAB – assuming that these mostly run more advanced process nodes

- 150 and 200mm FAB – typically running more mature and legacy process nodes

If you are working in a 300mm FAB:

Similarly, if you are working in a 150mm or 200mm FAB:

I will share the results of these pools in my next blog post – very much looking forward to see the numbers !

Test wafer management does come with one other challenge: low number of wafers in a carrier.

No matter which carrier type your FAB uses:

- 300mm FOUP

- 200mm SMIF pod with a cassette inside

- 150mm or 200mm box with a cassette inside

- 150mm or 200mm open cassette

Typically product wafer carriers contain more or less close to 25 wafers per carrier, while test wafer carrier very often do only have 1, 2 or 3 wafers inside.

It means that often a surprising large amount of carriers is occupied by test wafers and that requires a very controlled carrier management to not run out of available empty carriers (and storage places). I’m curious here as well, what is the overall situation nowadays in the FABs ?

If your are working in a 300mm FAB:

Similarly, for a 150mm or 200mm FAB:

Please provide some feedback using the polls if you have the needed data available. It will help to focus in my next blog post on the right topics.

If your not subscribed to my blog yet :

-

ASMC 2024

The Advanced Semiconductor Manufacturing Conference – short ASMC – will take place at a new venue this year. After many years in Saratoga Springs, NY this years conference will take place in Albany, NY.

Conference registration is open now and the reduced early bid fee is available only until 04/01/2024 !

direct link to the Conference webpage: LINK

I’m looking very much forward to this event for 2 reasons:

- Spring in Upstate NY is a beautiful season to meet and gather with industry peers from all over the world – if you come a few days early you have a chance to visit the Albany Tulip Festival

- listening to the latest news and trends in the semiconductor manufacturing world

The Conference Committee has put together a great line up of keynotes, technical sessions, panels and a poster reception. Here are a few of my personal highlights:

- Keynote from Vijay Narayanan (IBM fellow) about innovation in semiconductor in the AI area

- Keynote from Missy Stigal (VP Operations at Wolfspeed) about SiC

- Keynote from Robert Maire (President Semiconductor Advisors) – always a “must see & hear” about the latest developments in the industry

- Panel Discussion—Talent Pipeline: Building a Sustainable and Diverse Semiconductor Workforce

- Session 8: Smart Manufacturing + Industrial Engineering 1 – LINK

- Session 16: Smart Manufacturing + Industrial Engineering 2 – LINK

- Session 18: Factory Automation – LINK

Looking through old notes I realized ASMC 2024 will be my 20th ASMC – unbelievable how fast time flies!

ASMC 2004 took place in Boston, MA and I was a young and nervous engineer presenting my 1st paper – what a journey over the last 20 years !If you are curious what my paper was about in 2004:

But now lets look forward to ASMC 2024 – I hope I have the chance to meet many of you in person in Albany, NY in May !

-

THANK YOU 2023

Amazing how fast another year went by. I want to use the opportunity to say THANK YOU to all the followers and readers of my block. 2023 was again a very dynamic and successful year. Lots of good interaction on the subject of Factory Physics and Automation.

I wish you a great Holiday Season and hopefully I will see you all back in 2024 – here on these pages.

Speaking of 2024 – it already makes the news:

the 2024 Edition of the Innovation Forum in Dresden, Germany has lined up a great agenda: LINK

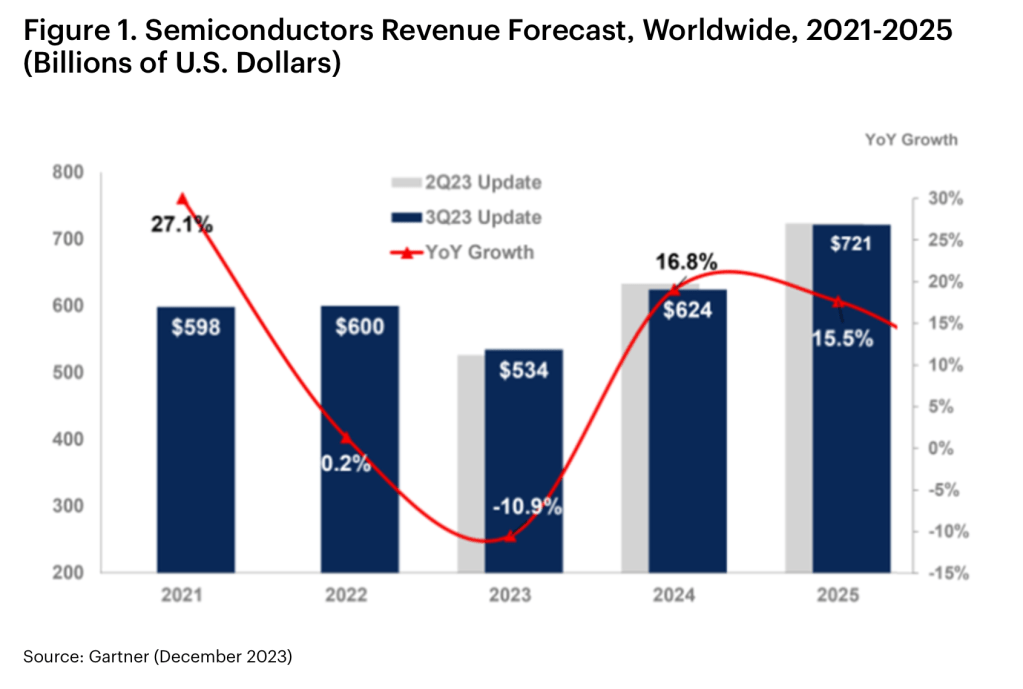

and the registration for this event is open: LINKalso – Gartner, Inc. forecasts that 2024 the semiconductor industry will be back on the growth track:

full article is here: LINK

-

Maintenance and FAB productivity

Today I save a lot of time typing – since there is a great article on the topic – written by McKinsey and Company.

As I have written about this topic in earlier posts – I can only recommend to read this piece as well:

On a related topic, a good old friend and former colleague of mine – Subramanian “Subbu” Pazhani – provided me as a guest author to the blog a great paper with the title

Analyzing Fab Bottlenecks – a Quantitative View

If you are interested to dive in a bit deeper on the impact of variability on equipment – hence FAB – performance, please have a look below.

Subbu is teaching Factory Physics at the NC State University in Raleigh, NC and a long time Factory Physics practitioner in the semiconductor industry. -

Impact of “time links” or controlled queue times

Today I like to discuss another potential FAB performance detractor – time links or controlled queue time zones. These got introduced to the more advanced process flows to avoid negative impact from long queue times between different process steps. Typical reasons for controlling length of queue times between steps are possible unwanted oxidation or corrosion on the surface of the wafer. These can have negative impact on overall wafer / chip yield and/or reliability.

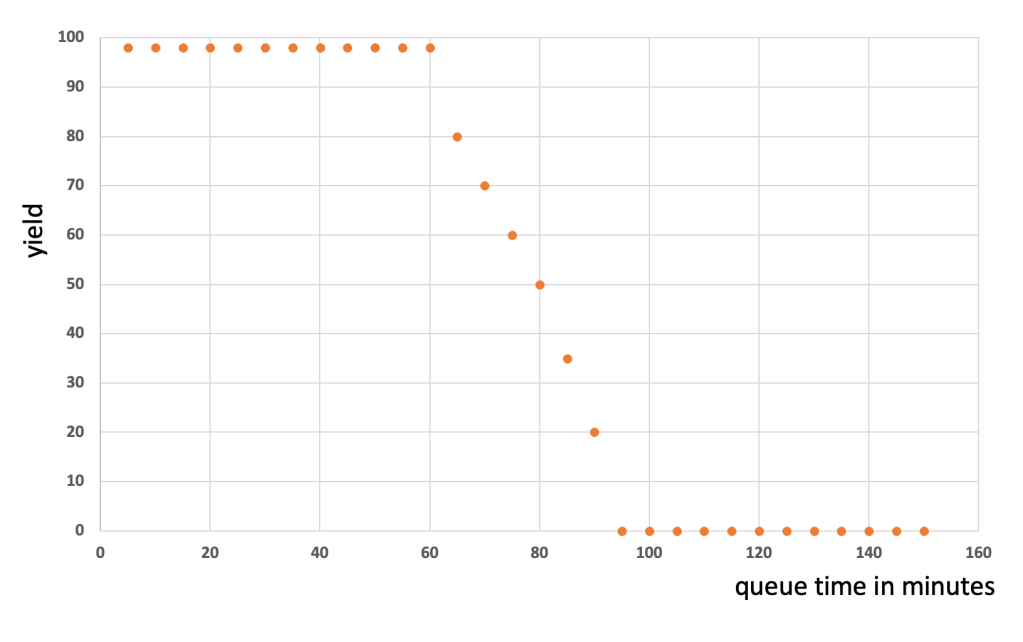

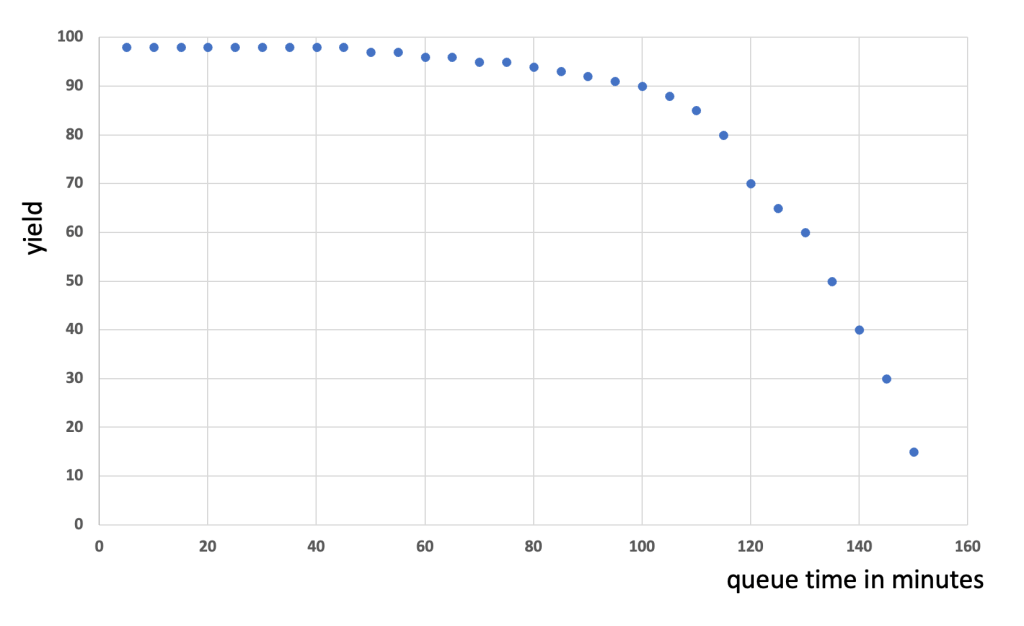

In the ideal case the process engineering team has detected such time sensitive behavior between process steps and created charts like the one below:

Based on the shown graph there is clearly a cliff starting after 60 minutes of queue time. The process team will very likely request from the manufacturing team that lots never wait longer than 60 minutes at in this zone. To be on the safe side the request might even be max. 45 minutes.

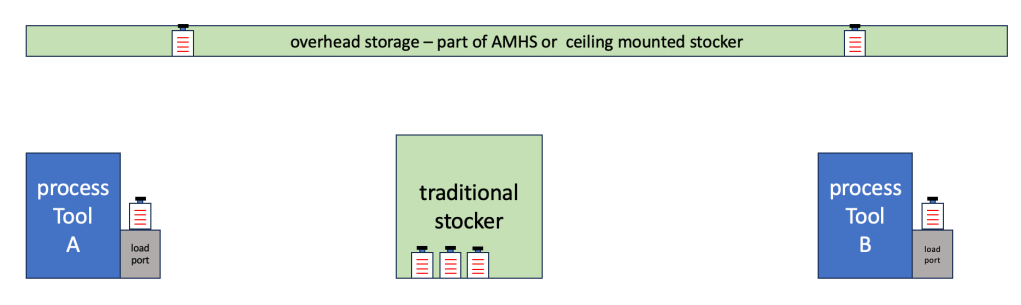

Lets have a look how such a time link zone is typically defined:

Time link zones are typically defined by a zone between a “trigger step” and the “target step”. The trigger step is the step in the process flow where the time link zone starts. A typical definition can be:

– the queue time starts, when the lot receives a operation complete – meaning all wafers at the trigger step on process tool A are completed and back in the carrier. The time would end when the lot receives an operation start at the target step on the target tool – in the picture above the process tool B.The idea is that all the time the lot / carrier is spending in transport, waiting in storage locations is counted towards that maximum allowed queue time, which should not be exceeded.

How can manufacturing manage this ?

In a nutshell: a lot will be only started at the trigger step / tool, when there is a guarantee, that the lot can be started at the target step within the given time boundary (in my example 45 minutes). This sounds pretty simple, but involves a lot of calculations and scheduling.

- on how many tools can the target step be processed

- how much WIP is in front of the target tool group waiting

- how long is the transport time between trigger and target step

- are there other higher priority lots in the time zone

- … many many more

There are many different ways in the FAB to manage this – from simple KANBAN approached to neuronal network based solutions. All of them have on thing in common: protect the wafers from too long wait time between trigger and target step. In a nut shell: the WIP flow will be controlled, which typically means slowed down.

There are 2 points in a flow where this happens:

1. for all time link lots at the trigger step – it will only be released onto the trigger steps if the zone is “empty enough” – hence each time the zone is not ready – the lot will wait.2. other lots waiting on the target tool, which are not in a time link zone ( on a different step in the flow) will have to give a time link lot priority – and therefore they have to wait even longer.

How big the overall impact on the FAB performance will be depends on a lot of things. Prominently these:

- shortness or length of the time link zone

- total number of different time link zones in a flow

- how risky the scheduler manages the time link zone

1. length of a time link zone

To define the “best length” is a tricky task. From a yield point of view shorter is better. From a manufacturing point of view longer is better. But not only that. In reality the yield degradation curves do not look that well defined like in the example from the top. Where to put the limit for the one below ?

Set the max allowed time to 45 minutes to be super safe – but likely have massive WIP flow impact ?

Set it for example to 80 minutes and take a yield hit ?

Another interesting aspect is the definition of the start and end time of the time link zone itself. The above used method of operation start of the target step and the operation complete of the trigger step is often not good enough for very sensitive processes.

Technically, the “bad environment influence” on the lot starts when the 1st wafer of the lot is finished with processing at the target step and is back in the carrier waiting for the other wafers of the lot.

For this 1st wafer the queue time ends, when it is back in the process chamber of the target step. The definition of the time link zone would be then: process complete of the trigger step until process start of the target step – at wafer level – not the lot level !

To manage time links on wafer level is a much harder challenge.

2. total number of different time link zones in a flow

Managing a single time link zone can be challenging, but if there are multiple zones with multiple steps and tool groups involved – it can become a challenging mathematical problem very fast.

Rule of thumb: More zones, more challenges and more impact on FAB productivity

Most mature processes often have only 1 or 2 time link zones – usually in the gate oxide and/or gate poly steps. Advanced process flows can have hundred or more time link zones!

3. how risky the scheduler manages the time link zone

In complex time link zones is no 100% guarantee that all lots “make it safely” in time to the trigger step. Too many factors and their variability will prevent the perfect solution.

A simple example is: If a target tool goes down, while there is planned WIP for this tool in the time link zone.

Therefore most algorithms use settings to calculate the probability of a lot making it in time to the target step. And the settings for these depend on many factors, again.

Rule of thumb: the higher the probability is set (lower risk) the more impact on FAB performance

Summary

Any time link zone in a flow will have impact on the FAB performance – just by the fact that every once in a while a lot has to wait at a target step.

How much the impact is depends on how much the FAB is willing to “pay for” avoidance of impact. Payment comes in one or more of these “currencies”:

- plan with lower tool utilization to provide buffer capacity

- invest in advanced scheduling (software, server, people)

- invest in Nitrogen purged storage solutions to extend the possible queue time

for example: OHT or stocker purge upgrades LINK

A great additional source on the subject of managing controlled queue times is the

FabTime Newsletter: Vol. 24, No. 2: Managing Time Constraints between Process Steps in Wafer Fabs

LINK -

MES & Industry 4.0 Summit in Porto, Portugal

What an event it was ! Critical Manufacturing organized on outstanding event – and I hope there will be a second one not too far in the future. About 500 experts met in Porto to discuss digitization and Industry 4.0 efforts. To me it was mind-blowing how much is going on in this area.

A key observation I had over the whole 2 days: There are big differences in how much progress different industries and companies have made so far.

One of the bigger challenges discussed multiple times is: How to calculate a realistic ROI for all the upfront cost to achieve a full digitization of a company or is this just a basic business enabler for future success ?

A first step to this journey is to understand where does your company stand today ?

I found this particular table from Jan Snoeij’s presentation very interesting to assess what manufacturing maturity level a company may have reached (1. being the lowest, 5. being the highest).

It is impossible to blog about all the great presentations and talks during the 2 days, but here are some of my favorites:

Jeff Winter Keynote: Transforming Manufacturing with Industry 4.0 – runtime about 38 minutes

Nicholas Leeder, The Smart Industry Readiness Index – runtime about about 30 minutes

Didier Chavet: The Role of AI in Manufacturing: Use Cases from the SEMI industry – runtime about 25 minutes

Francisco Almada Lobo: Stairway to Industry 4.0: a journey through hype and reality – runtime about 33 minutes

I had the honor to moderate a panel discussion on the topic of “Role of MES and IIoT in building resilient and data-driven enterprise” – runtime about 60 minutes

All presentations and recordings from the summit are available here: LINK

-

ASMC 2024 – call for papers

Next years Advanced Semiconductor Manufacturing Conference (ASMC) will take place in a new location. After many years in Saratoga Springs, NY ASMC 2024 will take place in Albany, NY.

Every year over 400 experts from the semiconductor industry meet at the conference to discuss and exchange about manufacturing challenges. Due date for this years call for abstract is October 10.

direct link to ASMC 2024 website: LINK

call for abstract flyer with all the key facts:

Since many years the conference is organized by a group of industry experts and seasoned semiconductor manufacturing professionals (LINK), all abstracts and papers are peer reviewed. Most of the committee members will be in person in Albany, NY – another great reason to attend to exchange with experienced peers in your field.

-

MES Summit in Porto, Portugal

I’m usually writing here about Factory Physics and (soon) Factory Automation topics. One major aspect of both is to have good data to understand the behavior of your FAB. Modern FABs are extremely complex “eco systems” and operating at “best performance” possible needs fast access to the “right” data. Key for this is for sure an advanced MES and more and more companies adding IoT elements to it.

I’m honored to moderate an expert panel at the MES Summit in Porto, Portugal which will dive into the IoT aspect

I will post about the event once I’m back.

It is still not to late to register : LINK

Here is a direct link to the agenda: AGENDA

Maybe I meet you in Person in Porto ?

-

2024 Innovation Forum for Automation

Today just a quick heads up: next years Innovation Forum for Automation will take place in Dresden, Germany on January 25 -25.

This year, there is a call for papers, so if you have an interesting project, problem or problem solution in the area of factory automation – the Innovation Forum could be a great stage for it:

Potential topics:

- Automated material handling & robotics

- AI, new automation approaches

- Energy efficiency /sustainability

- Shop floor automation for legacy Fabs

- Dispatching & scheduling

- Predictive manufacturing

Relevant Industries:

- Semiconductor

- Electronics

- Automotive

- Renewable Energies

please have a look here for the call for papers: LINK

and here is some background info on the Innovation Forum in general: LINK

-

Data is the new oil – or is it skilled workforce ?

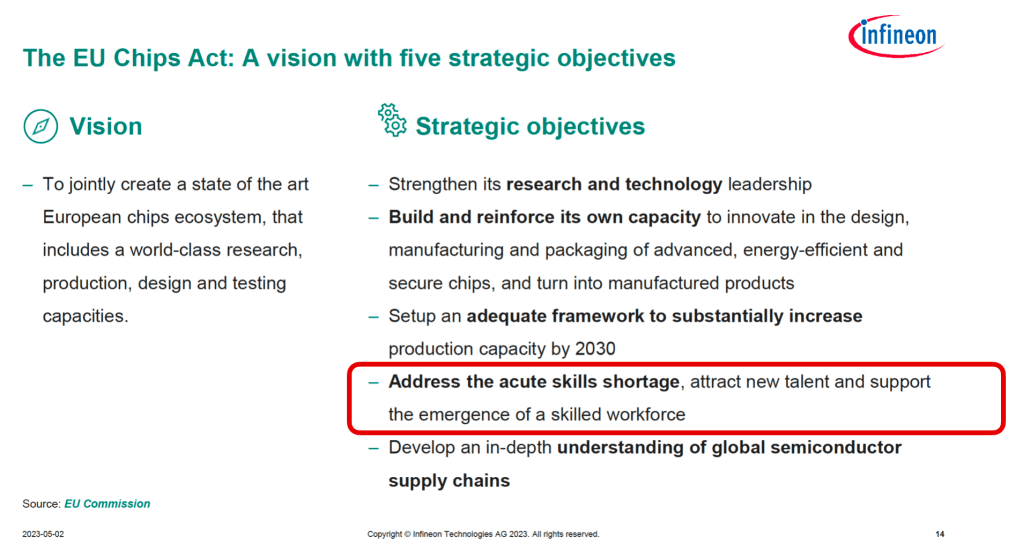

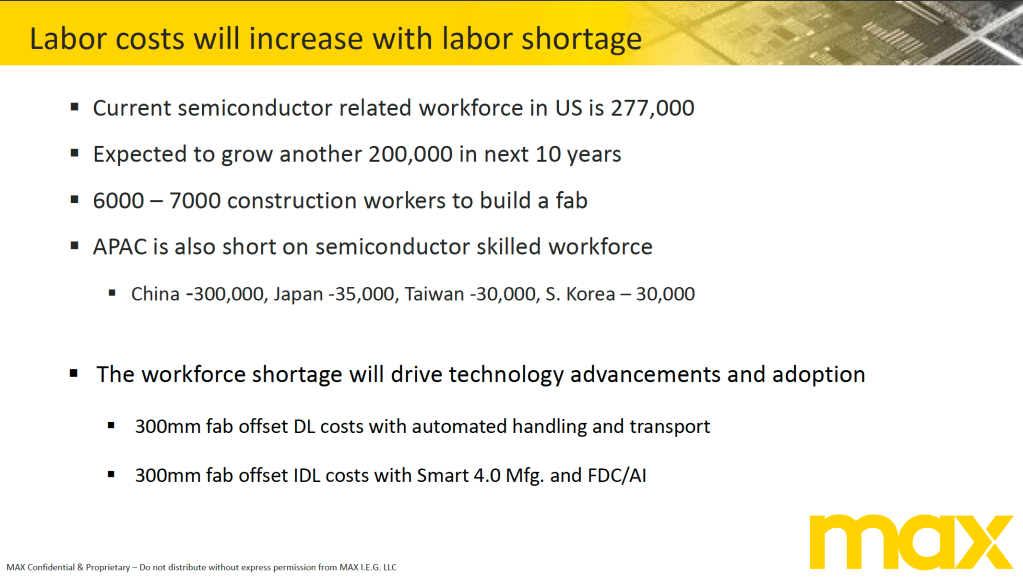

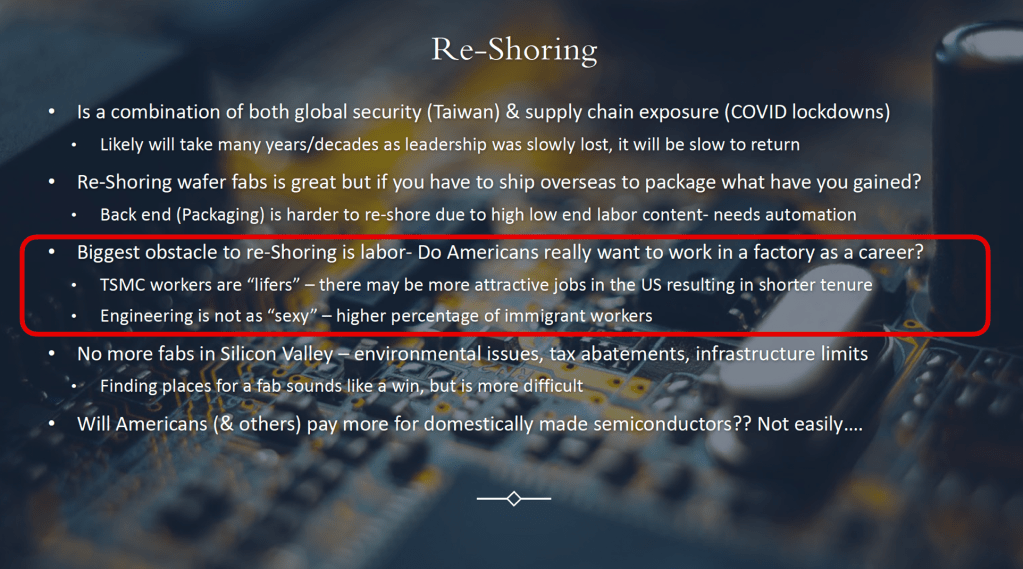

I just came back from the 2023 ASMC in Saratoga Springs, which was packed with 15 technical sessions and lots of great presentations. One topic was in the air throughout all the sessions – will the semiconductor industry have enough skilled operators, technicians and engineers ? Almost all keynotes brought this point up and there more I look at it the more I think the industries biggest problem in the next 5-10 years is the lack of skilled people.

Below are a few take outs from the presentations:

keynote Dr. Thomas Morgenstern, Infineon

keynote Thomas Sonderman, SkyWater Technology

panel discussion, Rick Glasmann, The MAX Group

keynote Robert Maire, Semiconductor Advisors

Robert Pearson, RIT

As a matter of fact, Roberts’ presentation sums up the situation perfectly and I got his permission to post it here:

Even the panel participants displayed a mirror image of the workforce situation. 3 out of the 4 panelists were seasoned Equipment Engineering / FAB veterans in contrast to the young AI / data expert. It really seems that the mechanical / electrical hands on work is slowly going extinct.

As one panelist shared with the audience: ” … I do have 3 kids, none of them want to work in the semiconductor industry …” asking about the why: ” … dad, look at you, you are always late back home, your are always stressed, the phone never stops ringing – why do I want to choose a life like this ? …”

The topic is serious – I think existentially serious. The semiconductor industry is extremely capital intensive and will only survive if the equipment in the FAB is running 24/7. Based on the numbers – showing the needed additional skilled workforce – it seems there will be many, if not all factories facing output and efficiency losses. But how much ?

Most forecasts show a delta of about 200,000 workers over a base of about 300,000 existing workers – that is a 40% gap. Depending on the specific field where the workforce is missing the impact will be different:

- missing operators in manual FABs will have massive direct impact – tools will not be loaded / unloaded in time and therefore there is direct loss in capacity and cycle time

- missing process technicians will have impact on hold lot release and overall process stability and therefore impact yield and reliability

- missing maintenance technicians and engineers will directly lead to less equipment uptime and lower equipment stability, both directly impacting FAB output, yield and reliability

- missing process engineers will lead to reduced process improvement work as well as to less stable manufacturing processes

- the list goes on and on

What will be the economical impact of all this ?

The total US semiconductor industry revenue in 2022 was in the neighborhood of $275 billion. If I just assume that a 40% shortage in skilled workforce will have a 10% overall impact (which I think is a extremely conservative estimate) that would mean, in the next 5 years there will be a loss of 5x $27.5 or

$137.5 billion

Even if my back of the napkin calculation is wrong by a factor of 2 or 3, this number is mind boggling – and it appears “nobody” really seems to take serious action – Why is that ?????

I guess, factors are ” it will affect not my company, since so far it has been not a major problem …” or ” .. if worst comes to worst, we can always raise salaries and get people from across the street …”

Nevertheless, if some companies might be less impacted, that means others are even more in a shortage. For the overall industry both scenarios are not good. The magic question is how to make jobs in semiconductor attractive again ?

Remember:

” … dad, look at you, you are always late back home, your are always stressed, the phone never stops ringing – why do I want to choose a life like this ? …”

Being myself a long time semiconductor addictive I fully can relate to that. It might be easy to say ” the young folks nowadays don’t like to work hard anymore …” – but false or true that will not change things. The semiconductor industry will be only more attractive for new technicians and engineers, if we change within the industry, what is seen as the problem by the next generations. The companies, which react and change first will have the best chances to again attract people.

Let me throw out a few possibly controversial thoughts here:

you are always late back home

Long hours have been a sign for hard work for way too long. If people need to stay on regular basis long hours, thats a sign for understaffing or bad organized / trained organizations. Unfortunately, reducing headcount numbers is seen as the easiest way to reduce cost. Too often, the quarterly hunt for good numbers – to keep Wall Street happy – leads to cuts, which are counterproductive in the mid and long run. Frequent downsizings – which are not uncommon in the semiconductor industry – are not a strong signal to attract the next generation of technicians and engineers.

–> rethink overall human resource strategies and become much more people centric (vs. pure head count efficiency, short term thinking)

–> incorporate impact of missing or not well trained workforce in all business model calculations to put hard $ numbers behind the effects (vs. assuming, people will be there when needed and set availability to 100%)

your are always stressed

Stress typically is generated, when people feel under pressure, since they can not control their job, but are controlled by overwhelming tasks and timelines. Outside of the general not enough people issue, key reasons are not enough know-how, training and resources to successfully do the job.

–> massively invest in training and standardization, people need to know what and how to do it

the phone never stops ringing

This is another “evil’ of the modern time: Always on, always connected and no clear rules for protecting employees personal time. This might be part of the general understaffing problem, but also not having enough experienced people, who can share the burden of on call and critical problem escalation support. During COVID people realized that there is also a life outside of work. Enjoying time with family becomes more and more important. If employers do not react people will leave or not even join to begin with.

–> how about guaranteed personal time with no contact from work and possibly a general 4 day work week ?

(imagine the company across the street starts to offer 4 day work week to attract people)

I still think the semiconductor industry can be very exiting to work in: There is plenty of fancy high tech “stuff” to be proud of, to be involved for all levels of education. Salary needs to be at least somewhat competitive. If people get rock solid training and career path, there should be no reason why people do not choose a career in semiconductor. Employment will be almost guaranteed in the next 10-15 years, looking at all the shortages.

I think these are the main levers to make semiconductor industry attractive again:

- massive image campaigns to the greater public and schools

- create opportunities for young people to understand what it means to work in a FAB

- community colleges and universities to offer the needed classes to study what is needed

– input and funding to come from the semi industry - seriously care about your people and get rid of the 24/7 grind with rules and appropriate staffing

- define semiconductor industry wide accepted job standards, which describe skills sets needed and certification levels

- training, training, training and clear career path visibility

This all will only happen if driven by the ones who have the problem in the first place – the semiconductor industry and universities that teach semiconductor engineering itself. It is not that the FABs should or can pay for everything themselves, but they need to start driving activities yesterday. Last but not least, programs like the CHIPs Act clearly need to involve workforce development with significant amounts, since else all the new FABs will not run as productive as planned . The result will be, that the attempt to bring semiconductor manufacturing back into the US will fail.

Super curious what you think about all this – please comment !

2 responses to “Data is the new oil – or is it skilled workforce ?”

-

Wie wahr, wie wahr.

Es bleibt spannend. Und die Frage nach dem Personal und anderen Resourcen bleibt offen.

Würde mich freuen, wenn wir uns bald mal wieder sehen würden.

Mit freundlichen Grüßen/best regards

Thomas Leitermann

+49 172 79 37 194

>

LikeLike

-

Very true. Many companies have not yet realized that it will become ever harder to get skilled employees.

Good point that new hires are not 100% up to speed immediately. For a maintenance technician the learning curve is 2 years. We need to factor this into financial considerations about “head count”. It is not only heads, it is skill. Lack of skill might become “apparent” only indirectly through yield excursions or too long maintenance times.LikeLike

Leave a comment

-

ASMC 2023

The Advanced Semiconductor Manufacturing Conference in Saratoga Springs is just one month away !

I’m looking forward to meet many industry experts and discuss Factory Physics topics in person. Here are some of my personal Agenda highlights:

- Keynote: Salvatore Coffa from STMicroelectronics – Silicon Carbide

- Keynote: Thomas Sonderman from SkyWater Technologies – US Chips Act

- Panel Discussion: Unintended Consequences of Government Subsidies on Moore’s Law and the Future of Semiconductors

and of course plenty of interesting technical presentations – these are some of my favorites:

- How to Teach Semiconductor Manufacturing and Why it is so Difficult

- Impact of Effective Technical Training in a Semiconductor Manufacturing Facility

- Automation in R&D: complying with contradictory constraints of seemingly incompatible world

- Granularity of Processing Times Modeling in Semiconductor Manufacturing

- Deploying an Integrated Framework of Fab-wide and Toolset Schedulers To Improve Performance in a Real Large-scale Fab

Hope to see you in person in beautiful Saratoga Springs, NY !

- Keynote: Salvatore Coffa from STMicroelectronics – Silicon Carbide

-

Product Mix and FAB performance

Semiconductor manufacturing is a highly complex and dynamic industry that requires constant innovation and adaptation to meet the changing needs of customers. One of the biggest challenges in this industry is managing changes to the product mix, which can have a significant impact on the overall efficiency and effectiveness of the manufacturing process.